Park and Yeom: Improving Emerging Infectious Disease Control Based on the Experiences of South Korean Nurses During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Systematic Review

Abstract

Purpose

This qualitative systematic review explored infection control by analyzing studies involving South Korean nurses who cared for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Considering the social and cultural differences between countries, it is necessary to understand the experiences of nurses in specific countries.

Methods

Articles published between January 2020 (the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic) and April 2022 were considered by searching six electronic databases. Thirteen articles were included based on specific inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Results

Through a thematic synthesis, six themes reflecting barriers to ensuring quality patient care during an emerging infectious disease situation were identified: lack of information and education about emerging infectious diseases, limitations in nursing infrastructure and system, physical stress owing to excessive nursing workload, mental stress owing to extreme anxiety about an infection, skepticism due to inadequate compensation, and ethical dilemma. Themes 1~4, which South Korean nurses experienced, were similar to the experiences of nurses in other countries. Themes 5 and 6 reflect experiences specific to nurses in South Korea.

Conclusion

To improve infection control against new infectious diseases, it is necessary to understand not only the similar experiences of nurses in all countries, but also experiences that are specific to each country's cultural and social characteristics. Thus, a distinct policy approach is needed for each country in order to improve infection control measures.

Key words: COVID-19, Infection control, Nurses, Review

INTRODUCTION

The novel 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory syndrome first reported on December 8, 2019, in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. It was subsequently declared a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 by the World Health Organization [ 1]. The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in South Korea was reported on January 20, 2020, and as of December 30, 2022, the total number of confirmed cases was 28,996,347, and the total fatalities were 32,095 (fatality rate of 0.12%) [ 2]. The South Korean government proposed the 3T (Test- Trace-Treat) epidemic prevention model to limit the spread of infection and additionally implemented strict social distancing regulations. South Korea presented an exemplary example to the international community via this 3T system consisting of “ Test” for testing and diagnosis, “ Trace” for epidemiological investigation and contact tracing, and “ Treat” for isolation [ 3]. The number of confirmed cases globally, however, increased sharply owing to community transmission. In South Korea, the number of daily confirmed cases reached a peak at 621,328 cases in mid-March of 2022 [ 2], and an average of 40,000 to 50,000 new COVID-19 cases were being reported every day [ 2]. Thus, the possibility of a new COVID-19 wave cannot be dismissed [ 2]. In a pandemic caused by an infectious disease, frontline nurses play a vital role in preventing the spread of COVID-19, inside and outside hospitals, through infection prevention and control and isolation measures [ 4]. Therefore, support systems and policies that enable healthcare workers, including nurses, to perform their vital roles adequately are essential. However, in previous studies that targeted nurses in various countries, support systems and policies mostly focused on patients with COVID-19 and not on healthcare personnel in clinical settings who treat these patients [ 5– 7]. Therefore, frontline nurses in each country experience physical [ 7], mental [ 5], and social stress [ 6]― including fatigue, lethargy, and anxiety― because of lack of rest and increased workload [ 5]. In particular, when a new respiratory disease such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) occurred in Korea in 2015, issues such as the establishment and management of hospitals dedicated to infectious diseases were raised, and nurses who cared for infectious disease patients did so without education on new infectious diseases or infection control guidelines [ 8]. However, the education of nurses was still not resolved in the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak, when confusion surrounded the treatment and management of infectious disease patients. Therefore, it is important to continue to identify barriers to improving infectious disease management in the current healthcare system and to make efforts to minimize barriers to managing emerging infectious diseases through the experiences of nurses who have cared for patients with actual infectious diseases such as COVID-19. In addition, since Korea values Confucianism differently from Western countries such as Canada, Australia, the United States, and Germany, and there are other social and cultural differences such as the number of patients cared for per nurse and annual salary and governments' responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have varied, nurses' experiences regarding COVID-19 might differ [ 9, 10]. Since a future re-emergence of COVID-19 or an outbreak of a different infectious disease could occur, a strategic and systematic plan is needed that considers the different social, cultural, and policy aspects of each country. It is necessary to systematically analyze and synthesize qualitative studies that explored the experiences of South Korean nurses who cared for patients with COVID-19 to identify a direction of improvement in infection control for providing optimal care during a possible re-emergence of COVID-19 or outbreak of any emerging infectious diseases. Therefore, we aim to provide evidence for the preparation of standardized nursing management guidelines and policy proposals for the management of emerging infectious diseases in the future.

METHODS

1. Design

The thematic synthesis methodology for qualitative systematic review was employed [ 11]. This methodology generates common themes by synthesizing findings in existing qualitative studies and clarifies the implications for future practice [ 10]. In addition, articles were systematically screened according to the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [ 12] and the PICO (Participant, phenomenon of Interest, Context, and Outcome) format was used for inclusion/exclusion of articles [ 13]. Institutional Review Board approval was not required since this study did not involve human participants. The study was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, and the PRISMA checklist is provided.

2. Search Methods

The key question of this study was, “ What is the infection control improvement plan for providing optimal care during a possible re-emergence of COVID-19 and outbreak of any new emerging infectious diseases?” Articles published between January 2020, which was the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, and April 2022 were reviewed. The word extraction was based on keywords used in previous studies. Using “ nurse” or “ nurse staff” or “ frontline nurse,” “ COVID-19,” or “ coronavirus,” and “ qualitative study” or “ qualitative research” as keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), six electronic databases (DBs), including three foreign (Ovid-EMBASE, CINAHL, and PubMed) and three Korean (KoreaMed, KMBASE, and KISS) DBs were searched.

3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) for participants, nurses who work in South Korean hospitals with experience in providing direct in-hospital care to patients with COVID-19; 2) for the phenomenon of interest, studies focusing on the experiences of these nurses; 3) empirical primary studies with qualitative research; and 4) articles published in Korean or English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) qualitative studies that focused on the experience of healthcare personnel other than nurses; and 2) studies that reported on the experience of providing care to patients with respiratory diseases (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome [SARS], Middle East Respiratory Syndrome [MERS], etc.) other than COVID-19.

4. Search Outcomes

A search strategy was selected before performing the qualitative systematic review. The initial draft of the search strategy was based on the articles searched in Ovid-EMBASE on January 2, 2022, using “nurse experience and COVID-19” as the search term. In addition, controlled MeSH or EMTREE terms were used because of the advanced search features of each DB, and text words used in the abstracts or titles were checked for inclusion in the search results; subsequently, the search terms were selected based on the text words. The literature search and analysis for selection and quality assessment were performed from January 2-April 30, 2022.

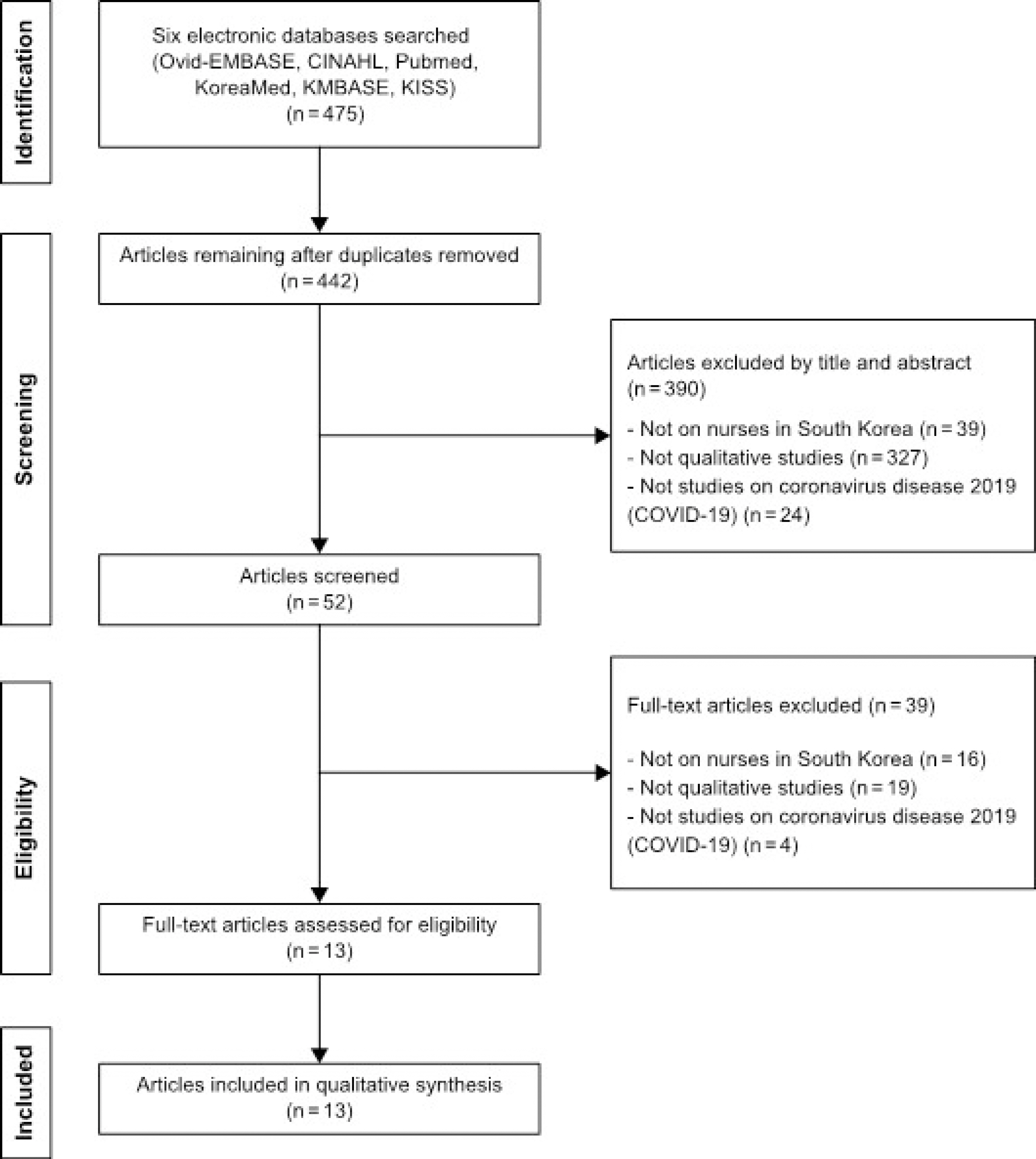

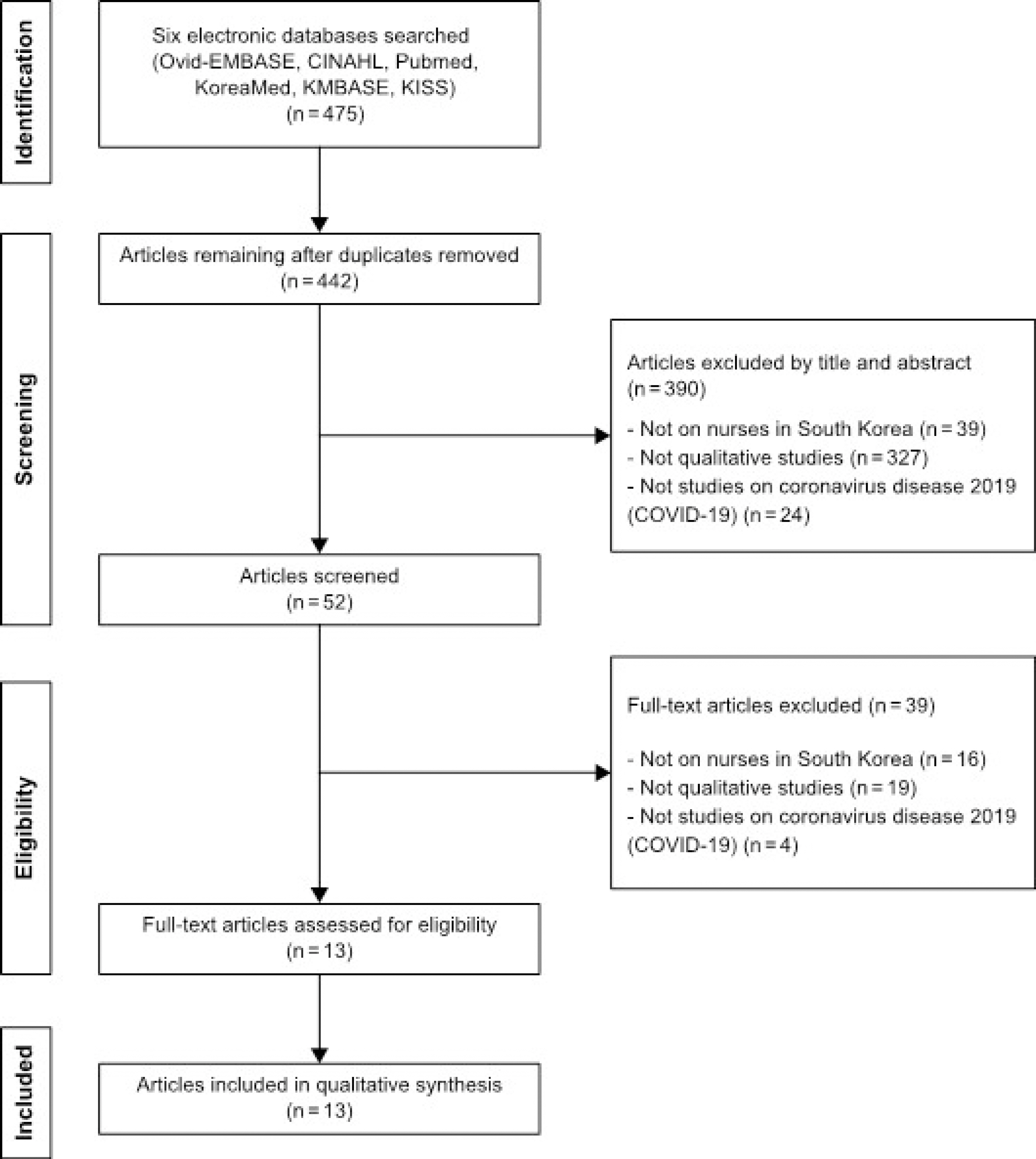

A total of 475 articles were identified. Subsequently, duplicates were removed manually and via a literature management program (EndNote X9). Two researchers reviewed the titles and abstracts of the remaining 442 articles and an additional 390 articles were excluded for the following reasons: 1) studies with participants who were not South Korean nurses, 2) studies that were not qualitative, and 3) topics that were not related to emerging infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Consequently, 52 articles were selected. After reviewing the full text of these articles, 39 were excluded based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, 13 were selected ( Figure 1).

5. Quality Appraisal

The Critical Appraisals Programme Qualitative Research Checklist [ 14] was used for the quality assessment of the 13 selected articles. The checklist is a generic tool for appraising the strengths and limitations of any qualitative research methodology. The tool has 10 questions that each focus on a different methodological aspect of a qualitative study [ 14]. The checklist included 10 questions assessing the aim of the study, qualitative design, recruitment strategy, data analysis and synthesis, findings, and overall research value. Each question can be rated as “ yes,” “ no,” or “ unknown.” After the first and second authors independently performed quality assessment, the results were compared, and any disagreement was resolved through discussions. Finally, a third person― a nursing professor― reviewed the results again. All 13 selected articles were assessed to have appropriate methodological rigor.

6. Data Abstraction

One researcher constructed the framework for data extraction of the experiences of South Korean nurses who cared for patients with COVID-19. Subsequently, two researchers independently analyzed and extracted the data. The categories used for data extraction were author, year, setting, country, aims, sample, sample characteristics and methods, study design, data collection and analysis methods, and major findings [ 15– 27] ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies (N=13)

|

Author (year) Setting Country |

Study aim |

|

|

Major findings |

|

1. Kim et al. (2022) [21] Hospital South Korea |

To understand the experiences of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19. |

|

|

Struggling to prepare an infection ward Fear and anxiety about infection The weight of pressure from patient care Efforts to protect patients Maturity of professional identity as a nurse A quarantine community that we create together

|

|

2. Chung et al.(2022) [16] Hospital South Korea |

To explore nurses’ experience in caring for patients with COVID-19. |

|

|

|

|

3. Ha et al.(2022) [17] Hospital South Korea |

To understand and describe the experiences of nurses in charge of COVID-19 screening at general hospitals. |

|

|

Hospital gatekeeper entrusted with managing the COVID-19 pandemic Struggling to maintain the protective barrier Boundlessness and drive like a Mobius strip Force to endure as a nurse in charge of COVID-19 screening

|

|

4. Kim, Cho.(2021) [20] Hospital South Korea |

To examine the emotions experienced by South Korean clinical nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic and to understand their essential meaning in-depth. |

|

|

Shock of the unprecedented new infectious disease Hardships caused by the never-ending struggle Hope in the midst of hardship

|

|

5. Lee, Song.(2021) [23] Hospital South Korea |

To develop a situation-specific theory to explain nurses’ experiences of the COVID-19 crisis. |

|

|

Chaos of being exposed defenselessly to an unexpected pandemic Fear caused by a nursing care field reminiscent of a battlefield Moral distress from failing to protect patients’ human dignity

|

|

6. Noh et al.(2021) [24] Hospital South Korea |

To explore nurses’ experience with caring for patients with COVID-19 in a negative-pressure room amid the spread of the pandemic. |

|

Qualitative study Focus group interview Thematic analysis

|

|

|

7. Oh et al.(2021) [26] Hospital South Korea |

To explore nurses’ working experiences during the pandemic at a COVID-19 dedicated hospital. |

|

|

Hesitating to move forward Standing up with the name of nurse Experiencing unfamiliarity and confusion “Walking on thin ice” every day Getting used to working Growing one step further Being left with unsolved issues.

|

|

8. Kim.(2021) [19] Hospital South Korea |

To investigate the nurse's practical experience on the COVID-19 patient care in the infectious-disease hospital. |

|

|

Uncared-for patients in the care site as unprepared and unfamiliar Exhaustion owing to extreme anxiety and stress Best quality care for patients with COVID-19 Become accustomed with taking care of patients with COVID-19 Effective reflection of taking care of patients with COVID-19.

|

|

9. Park, Chio.(2021) [27] Clinic South Korea |

To explore the meaning of nurses’ experiences of working at Drive-Thru COVID-19 Screening Clinic. |

|

|

A sense of calling as a nurse Physical and psychological stress Daily life adapted to the work of the screening clinic Time to live together in the fight against the virus New perception and rewards for nursing

|

|

10. Oh, Lee.(2021) [25] Clinic South Korea |

To understand nurses’ actual experiences of caring for patients with COVID-19. |

|

|

A repetitive sense of crisis Enduring a drastic change Sacrifice of personal life Pride in nursing.

|

|

11. Lee, Lee.(2020) [22] Hospital South Korea |

To explore the experiences of COVID-19~designate d hospital nurses who provided care for patients based on their actual experiences. |

|

|

Pushed onto the battlefield without any preparation Struggling on the frontline Altered daily life Low morale Unexpectedly long war on COVID-19 Ambivalence toward patients Forces that keep me going Giving meaning to my work Taking another step in one's growth

|

|

12. Jin, Lee.(2020) [18] Hospital South Korea |

To increase professionalism in nursing and effective counter-strategies against future infectious diseases. |

|

|

COVID-19 came without preparation Nursing work and sense of vocation Life changed with COVID-19.

|

|

13. Choi, Lee.(2020) [15] Hospital South Korea |

To help managers in nursing hospital understand their work in the event of an infectious disease, and to provide basic data for improving response strategies and infection control systems in the future when new infectious disease occurs. |

|

|

Inadequate initial response Infection management became a daily life Focusing on preventing COVID-19 infection through education Atrophy of emotions vs. blocking the infection route Reinforcement of cooperation with local healthcare teams Infection disease response direction in nursing hospitals

|

7. Synthesis

For data synthesis, a thematic analysis and synthesis developed by Thomas and Harden [ 11] was used to find recurring themes in the 13 selected articles. Each theme was synthesized using a three-step approach: 1) initial codes were generated from the selected studies, 2) descriptive themes were extracted from the codes based on similarity, and 3) themes were summarized and reviewed. Two researchers extracted the codes and themes, twice for each study to assure methodological rigor. Subsequently, one researcher reviewed the codes and themes, and all researchers reached a consensus via discussions. Therefore, we tried to ensure that the review results were firmly based on the original data so that the results reflected the experiences of the original participants.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses flow diagram of the literature search.

RESULTS

1. Study Characteristics

Among the 13 articles [ 15– 27], three (23.1%) were published in 2020, seven (53.8%) in 2021, and three (23.1%) in 2022. Twelve articles were published in Korean and one in English. The selected studies included 174 nurses with experience in providing in-hospital care to patients with COVID-19. Nurses’ age ranged from 20~63 years and clinical experience ranged 1~28 years. However, Park et al. [ 27] did not report the mean age and clinical experience of participants. All 13 articles were qualitative studies, which satisfied the quality assessment criteria, and were rigorously conducted. Based on data collection method, nine studies (69.2%) employed face-to-face in-depth interviews, two (15.4%) employed in-depth telephonic interviews, and two (15.4%) employed focus group interviews. Based on data analysis methods, six studies (46.2%) used the Colaizzi analysis, five studies (38.5%) used content analysis, one (7.7%) used thematic analysis, and one (7.7%) used data analysis ( Table 1).

2. Main Findings

Six areas that needed improvement were identified through thematic synthesis: 1) lack of information and education about emerging infectious diseases, 2) limitations in nursing infrastructure and system, 3) physical stress owing to excessive nursing workload, 4) mental stress owing to extreme anxiety about an infection, 5) skepticism due to inadequate compensation, and 6) ethical dilemmas. Among these, Themes 1~4 were similar experiences that nurses in each country had while providing care to patients with COVID-19, as shown in previous results [ 5, 7]. However, Themes 5 and 6 were different experiences that South Korean nurses had ( Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Similarities and Differences in Thematic Analysis

|

Main themes |

Codes in the texts |

|

Similar experiences |

Lack of information and education about emerging infectious diseases |

․ Caring for COVID-19 patients suddenly without COVID-19 infection control guidelines and education [15,17,19–23,25] |

|

․ No infection control education for non-healthcare workers, such as auxiliary personnel [14,15] |

|

Limitations in nursing infrastructure and system - Material and human resources |

․ Shortage of PPE for healthcare workers [15,16,18–21,23,25,27] |

|

․ Shortage of skilled nursing staff to deal with the increase in the number of infected patients [15,18,19,21–24,26] |

|

․ Unstable operating system throughout the hospital, such as constantly changing work schedules, disease control guidelines, and environmental management methods [15–18,20,22–24] |

|

․ Establishment of temporary infection ward owing to shortage of negative-pressure and isolation units [16,17,20,21] |

|

․ Lack of a system for checking patient condition and timely response [24,25] |

|

Physical stress owing to excessive nursing workload |

․ Physical exhaustion owing to excessive workload while wearing PPE [15,17–19,21,22,24–26] |

|

․ Requirement to handle work for other departments and additional work owing to staff members placed under self-isolation [15,16,18,19,21,24] |

|

․ Unreasonable demands and verbal abuse from patients and guardians [15,17,18,21,22,24] |

|

․ Added burden from unfamiliar work and diverse inpatients, including regular patients, patients with dementia, and foreign patients [15,20,22,25] |

|

․ Feeling helpless and exhausted owing to the continuing pandemic with no end in sight [16,17,20,22,26,27] |

|

․ Reducing food and water intake during work owing to difficulties in going to the restroom [17,18,23,25,27] |

|

Mental stress owing to extreme anxiety about infection |

․ Anxiety about becoming infected or infecting others family members, coworkers, etc. [15–21,24–27] |

|

․ Social isolation from minimizing outside activities and self-isolation [16–19,22,25] |

|

․ Repeating the behavior of obsessively checking PPE and personally trying on PPE [21,24,26] |

|

․ Disappointment from distorted view by others [16,22,23,27] |

|

Different experiences |

Skepticism due to inadequate compensation

Ethical dilemma |

․ No hazard pay or appropriate reward system [16,18–20,22,23,25] |

|

․ Efforts and sacrifices of nurses taken for granted [19,21,23,26] |

|

․ Requirement to fulfill all responsibilities as a nurse despite being afraid and tired [26,27] |

|

․ Experiences of the death of patients who did not receive proper respect under the pretext of infection prevention [16,23,26] |

|

․ Dilemma related to CCTV monitoring that did not protect the privacy of patients [27] |

3. Theme 1: Similarities in Experience-Lack of Information and Education about Emerging infectious Diseases

In seven studies [ 15, 17, 19, 21– 23, 25] the general ward nurses stated that they experienced frustration and apprehension after being assigned to the COVID-19 ward without any guidance, education, or preparation. In Kim et al.[ 21] nurses stated that they became frantic and lacked information on emerging infectious diseases and education on methods of donning/doffing personal protective equipment (PPE), hand sanitation, and infectious-disease ward conditions. In Lee and Lee [ 22] nurses mentioned that they were assigned to the COVID-19 wards without receiving sufficient training to care for patients, and upon questioning the disease control headquarters, they received the response: “ We don’ t know. Do as you see fit. Nothing has been set.” These situations made them fearful. In addition, two other studies reported that infection control education for auxiliary personnel other than medical personnel was not conducted in all hospitals. In Chung et al.[ 16] nurses reported that their anxiety and confusion worsened as they observed auxiliary personnel's negli-gent attitude toward infection control protocols. In Choi and Lee [ 15] nurses reported that it was tedious to repeatedly educate auxiliary personnel and check their conduct. Despite this, the nurses self-studied and performed their professional duties, in addition to their personal work and adhered to hospital guidelines to respond quickly for patient care [ 17]. Nurses with experiences in caring for patients with infectious diseases, such as MERS and COVID-19, emphasized the need for systematic and specified education and mentioned the importance of establishing standardized nursing guidelines for such cases [ 18, 19, 24].

4. Theme 2: Similarities in Experience-Limitations in Nursing Infrastructure and System

During COVID-19, the nurses indicated a lack of nursing infrastructure, such as material and human resources, and an inconsistent hospital management system. In nine studies [ 15, 16, 18– 21, 23, 25, 27], the nurses mentioned shortage of PPE, such as N95 masks and protective suits, that were essential for patient care. In Kim et al. [ 21], nurses reported that they used N94 or dental masks owing to shortage of masks (mask crisis) in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. In Jin and Lee [ 18] nurses expressed that they received a single N94 mask per day, and later, owing to extreme shortage, masks were re-worn for 2-3 days. In Park and Choi [ 27], nurses reported that they avoided going to the bathroom because doffing the PPE would require discarding it. Four studies reported that the nurses struggled in setting up an infection ward by discharging general patients or transferring them to other hospitals owing to lack of beds with isolation facilities for treating infected patients [ 21]. Additionally, they experienced anxiety as they cared for patients in a general ward without negative-pressure facility [ 16]. Nine studies noted that shortage of skilled nursing personnel became a problem after a sudden increase in the number of patients with COVID-19. This resulted in the self-isolation of some healthcare workers. Consequently, the workload increased as vacancies created were left unfilled [ 16], however, even when these vacancies were filled, the newly deployed replacement nurses had neither a proper knowledge of supplies nor knew sample collection methods [ 20, 21]. Duties that changed daily owing to consistently changing infectious-disease response guidelines, reassignment, and inter-departmental coordination of duties caused much confusion [ 18]. Nurses additionally emphasized the need for improving monitoring systems, including closed circuit televisions (CCTVs), for checking patient conditions and providing timely responses [ 24].

5. Theme 3: Similarities in Experience-Physical Stress Owing to Excessive Nursing Workload

In nine studies [ 15, 17– 19, 21, 22, 24– 26], nurses reported that donning Level D PPE tested their tolerance limits. In Oh and Lee [ 25], nurses mentioned that they were “ soaked with sweat” as they frantically worked while bumping into things owing to a narrow visual field and awkward and uncomfortable movement owing to donning an unfamiliar PPE, three layers of gloves and goggles, which was akin to wearing a space suit. In Jin and Lee [ 18], nurses stated that they tried to limit their food intake to minimize going to the bathroom since they could not do so freely after donning the Level D PPE. In addition, because infection wards had restricted access to guardians and care-givers, patients and guardians sometimes made unreasonable requests. In Kim et al. [ 21], nurses were inundated with excessive requests from patients, such as delivery and food errands, while concerned guardians often inquired about sensitive patient information. Consequently, activities other than patient care presented difficulties. In addition, despite that hospitals had various other healthcare personnel, including doctors, radiologists, and clinical pathologists, some were reluctant to enter the infection ward owing to the risk of infection, complexity of procedures, and PPE use. The nurses mentioned by Kim and Cho [ 20] reported that they experienced confusion and felt overworked from having to additionally perform the duties of other healthcare personnel, such as hospital room cleaning, providing care for critically ill patients, and sample collection because of the aforementioned reasons. As community outbreaks of COVID-19 infection continued to occur and the pandemic had reached the nth wave with repeated increase in number of confirmed cases, nurses felt overwhelmed by the unending pandemic and complained of physical difficulties from the uncertainty of the duration of their work [ 17].

6. Theme 4: Similarities in Experience-Mental Stress Owing to Extreme Anxiety about Infection

In 11 studies [ 15– 21, 24– 27], nurses were apprehensive about being infected and feared spreading the infection. They were more concerned about infecting others and causing a chain of infections. In Oh and Lee [ 26], nurses attempted to quell their anxiety by getting themselves tested whenever they felt slightest throat pain, bathing at home even though they had washed themselves at the hospital before leaving, and repeatedly imagined donning/doffing the PPE. In Park and Choi [ 27], nurses reported that they refrained from socializing, and on days after their shift, they self-isolated themselves, eating alone. In Kim and Cho [ 20], nurses mentioned that being self-isolated felt lonely and unfamiliar at times. In Chung et al.[ 16], nurses reported that they experienced disappointment in their being perceived as sources of infection based on the fact that they worked in COVID-19 wards.

7. Theme 5: Differences in Experience- Skepticism due to Inadequate Compensation

In nine studies [ 16, 18– 23, 25, 26], the nurses expressed skepticism due to inadequate compensation, which was supposedly relative to their best patient-care efforts. In Kim and Cho [ 20], nurses mentioned that there was no hazard pay or an appropriate reward system and that they felt troubled about their sacrifices not being adequately acknowledged. In Jin and Lee [ 18], nurses mentioned that they had provided high-quality patient care, performed supply and hospital management duties, and performed disinfection with a sense of professionalism; however, compared to their efforts, the compensation they received was inadequate.

8. Theme 6: Differences in Experience-Ethical Dilemmas

Nurses faced an ethical dilemma between a sense of vocation and human dignity. In two studies [ 26, 27], nurses wanted to avoid caring for patients with COVID-19 owing to fear of possible infection and an excessive workload; however, they cared for patients because of their sense of professional responsibility. According to Park and Choi [ 27], though the general nurses felt burdened and were concerned about working in screening centers, they even-tually signed up owing to their duties as nurse managers. In four studies [ 16, 23, 26, 27], nurses experienced anguish and regret owing to patients not receiving proper respect after their death on the grounds of infection prevention. In Oh et al.[ 26], nurses expressed bitterness as they observed patients dying alone without family and plastic-wrapped corpses on cold concrete floors next to waste disposal boxes to be awaiting transportation owing to the stringent protocols for infection control. In Kim et al.[ 21], nurses faced the dilemma of monitoring the condition of patients via CCTV since they could not continuously stay in the isolation room; although this was beneficial for timely responses in cases of critically ill patients, it was an invasion of patients’ privacy.

DISCUSSION

The following six areas in need of improvement for enhanced quality of patient care during future re-emergence of COVID-19 and outbreaks of any new infectious disease were identified.

“ Lack of information and education about emerging infectious diseases” was identified as the first area requiring improvement. This was a common experience not only for South Korean nurses who cared for patients with COVID-19 but also for nurses from many other countries [ 5– 7]. Professional infection control education for nursing students can reduce infection-related anxiety and improve infection management competency [ 28]. Nurses assigned to care for patients with COVID-19 in-dicated a lack of information on emerging infectious diseases treatment and inadequate infection control education for in-hospital healthcare and other auxiliary personnel. In South Korea, nurses who experienced the 2015 MERS outbreak alluded to difficulties in correctly donning and doffing Level C/D PPEs; additionally, they feared and questioned whether patients received appropriate quality of care, owing to lack of treatment-related information, including route of infection, prognosis, treatment method, isolation, and cooperation [ 8]. A study investigating the need for education on emerging infectious diseases reported that among 162 South Korean nurses with no experience in caring for such patients, 93.2% wished to participate in educational programs related to infection control for these diseases; specifically, clinical practice-oriented education that can be immediately applied including treatment and care for emerging infectious diseases, isolation method, and order of donning/doffing PPE [ 29]. This indicates the need for systematic and repetitive infection prevention and control education (e.g., PPE donning/doffing, N95 mask fit test and wearing method, and route of infection, by type of infectious disease) through hands-on training. “ Limitations in nursing infrastructure and system” was identified as the second area requiring improvement. This was also a common experience of all nurses, including South Korean nurses who provided care to patients with COVID-19[ 5– 7]. Nurses stated that insufficient material and human resources and an inconsistent hospital management system were factors undermining infectious disease patient care. Nurses who worked with newly recruited, untrained (owing to staffing shortage) nurses were stressed when providing patient care and experienced a sense of crisis and deliberated on resigning owing to the additional workload to compensate for staffing shortages [ 30]. These ultimately led to the loss of professional staff and to a vicious cycle with yet more workload for the remaining nurses. Hence, availability of skilled nursing staff is crucial. Therefore, training and encouraging professional infection specialist nurses who provide high- quality care to patients with infectious diseases and perform a key role is essential. Moreover, increased anxiety among nurses who care for high-risk patients (e.g., COVID-19) was caused by shortage of supplies, frequent work schedule and environmental management procedural changes owing to the inconsistent hospital management system [ 21]. Accordingly, measures to provide uninterrupted medical supplies during outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases, and consequently, long-term preparations to improve safety measures for nurses and other healthcare personnel are needed to minimize exposure to infection. Additionally, nursing standardization and hospital-based systematic practice guidelines are also needed to minimize confusion in nursing. “ Physical stress owing to excessive nursing workload” was identified as the third area needing improvement. This was also a common experience of all nurses, including South Korean nurses who provided care to patients with COVID-19[ 5– 7]. Level D PPE suits tested nurses’ endurance limits, and in addition to patient care, their duties included performing tasks of other healthcare workers, ward disinfection, and cleaning. These findings were consistent with a previous study reporting that nurses experienced physical exhaustion owing to increased workload and long work hours during the MERS outbreak [ 8]. The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in more confirmed cases and fatalities and has persisted longer than the SARS global epidemic in 2000 and the MERS outbreak. Consequently, nurses have experienced even higher physical exhaustion [ 31]. Hence, sufficient nurse staffing and clear delegation of work among healthcare workers during infection outbreaks must be prioritized to ensure an equal distribution of workload. Moreover, consideration and cooperation among peers and support from managers are viewed as motivational factors for nurses [ 16], hence, an organizational culture that can strengthen inter-personnel and departmental cooperation must be emphasized. “ Mental stress owing to extreme anxiety about infection” was identified as the fourth area needing improvement. This was also a common experience of all nurses, including South Korean nurses who provided care to patients with COVID-19 [ 5– 7]. Previous studies reported that anxiety, stress, and depression increased during the COVID-19 pandemic than during pre-COVID-19 outbreaks [ 32]. Nurses feared infecting others, such as coworkers or family members, and were distressed because people regarded healthcare workers caring for patients of COVID-19 as an infection source. Consequently, nurses experienced long-term depression and social isolation. Further, nurses caring for patients with an infectious disease experienced extreme mental stress that caused insomnia, in addition to depression and anxiety [ 25, 31]. Discussions on effective coping strategies are unavailable; therefore, these findings suggest that considerable interest in alleviating the mental stress of these nurses and in studies on stress coping programs, which include personal aspects such as emotional support from family and coworkers is needed. Establishment of a foundation for overcoming challenging situations by building a social and emotional support system for nurses through multi-dimensional efforts is necessary. “ Skepticism due to inadequate compensation” was identified as the fifth area needing improvement. This was the experience of South Korean nurses that differentiated from nurses in Canada, Germany, Australia, the United States and other countries. Nurses complained about the compensation system. In South Korea, the number of clinical nurses working in domestic medical institutions in 2020 was 7.9 per 1000 population, lower than the Organization for Economic cooperation and Development (OECD) average of 9.4, Germany's 13.9, Australia's 12.2, Japan's 11.8, and the UK's 8.4[ 33]. In addition, the average annual remuneration of hospital nurses in South Korea is $40,100, which is lower than the OECD average of $48,100, $79,000 in the U.S., $67,900 in Australia, and $57,700 in Canada [ 33]. In the recent pandemic, clinical nurses in South Korea did more work than usual with low pay, which caused a social problem that greatly increased the turnover rate of nurses [ 34]. Effort-reward imbalance is a factor that increases the fatiguability of nurses [ 35]. Therefore, failure to implement appropriate reward systems during a pandemic could increase nurses’ mental stress and potentially affect the quality of patient care. These frontline nurses were not fairly compensated despite performing additional work that endangered their safety. Therefore, especially for South Korean nurses, an improvement in the overall reward system is needed to ensure that nurses who work in a hazardous environment have adequate financial support to enhance their role in the field. “ Ethical dilemmas” was identified as the sixth area requiring improvement. This was also an experience of South Korean nurses that differentiated from nurses in other countries. Pandemic scenarios inherently raise these dilemmas for all healthcare workers, particularly nurses [ 36, 37]. In particular, the public response to South Korean and American nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 differed owing to social and cultural differences [ 8]. While American nurses recalled positive experiences, such as fleeting heroism, South Korean nurses recalled negative experiences, such as the public stigma of being frontline nurses [ 9]. Nevertheless, as they cared for patients with COVID-19, nurses experienced the dilemma of dealing with their professional responsibilities and empathizing with patients. Ethical dilemmas can cause post-traumatic stress owing to moral distress and lead to fatiguability among nurses when incorrectly managed [ 38]. Enhancement of moral resilience can aid in the management of moral distress [ 38]. Therefore, there is a need for confidence- instilling programs that allow South Korean nurses to courageously face painful and uncertain situations according to their own ethos. This study is the first to analyze and synthesize qualitative studies on the experiences of South Korean nurses who cared for patients with COVID-19 to identify potential areas in nursing needing improvement that are required in South Korea to ensure quality patient care during future outbreaks of infectious diseases.

South Korean nurses who experienced COVID-19 had experiences similar to nurses in other countries but also had different experiences owing to social and cultural differences. Based on the findings, the following measures are recommended: first, to solve the effort-reward imbalance of South Korean nurses, improvement of the policy reward system should be prioritized. Second, a program for reducing various moral distresses that can strengthen the moral resilience of South Korean nurses is needed. Third, since a one-time training course in infectious diseases will not provide the requisite skills and expertise, systematic and continuing education on infectious-disease prevention and control is recommended for all healthcare workers, including auxiliary personnel and nursing students. Fourth, increasing the number of professional nursing personnel and improving attitudes toward nurses are recommended for enhanced quality of patient care, particularly during epidemics or pandemics. Lastly, policy studies for formulating standardized practice guidelines through collaboration between public health workers, healthcare institutions, and health authorities are recommended for future infectious-disease control.

1. Limitations

A limited number of studies were included in this review, and the study population was restricted to South Korean nurses; therefore, caution is needed when generalizing the findings in the broader international context. Further, the authors reviewed articles published in Korean and English; therefore, the essence of the original studies in different languages may have been lost in translation. In addition, while the experiences of nurses with COVID-19 patients may not be comprehensive of all emerging infectious diseases, we believe that the global experience of the COVID-19 pandemic can be used to prepare strategies to minimize barriers to ensuring quality patient care in the event of another emerging infectious disease outbreak.

CONCLUSION

South Korean nurses caring for COVID-19 patients, like nurses in other Western countries, had similar experiences such as fear of infection, confusion, extreme physical and mental stress, and fatigue due to poorly prepared quarantine systems at the beginning of the pandemic. However, due to the social and cultural characteristics of Korea, South Korean nurses had different experiences such as skepticism about unsupported compensation and ethical dilemmas. Therefore, in order to improve infection control for emerging infectious diseases, other unique experiences that take into account the social and cultural characteristics of each country must be understood, and differentiated policy approaches are needed to improve them. Based on the findings of this study, further research is needed to develop standardized nursing management guidelines and healthcare policy suggestions to minimize barriers for frontline nurses caring for patients with infectious diseases.

REFERENCES

2. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022b. [cited 2022 Dec 11]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

7. AI Thobaity A, Alshammari F. Nurses on the frontline against the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrative review. Dubai medical Journal. 2020; 3(3):87-92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000509361

12. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery. 2021; 88: 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

13. Pettigrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide.. 1st ed.. Malden: Blackwell; 2006. p. 29-93.

15. Choi KS, Lee KH. Experience in responding to Covid-19 of nurse manager at a nursing hospital. The Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2020; 21(11):1307-1322. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.11.5.94

17. Ha BY, Bae YS, Ryu HS, Jeon MK. Experience of nurses in charge of COVID-19 screening at general hospitals in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2022; 52(1):66-79. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21166

18. Jin D, Lee G. Experiences of nurses at a general hospital in Seoul which is temporarily closed due to COVID-19. The Journal of Korean Academic Society of Nursing Education. 2020; 26(4):412-422. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2020.26.4.412

19. Kim K. A phenomenological study on the nurse's COVID-19 patient care experience in the infectious disease hospitals. The Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2021; 21(12):2145-2160. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.12.5.151

20. Kim DJ, Cho MY. Korean clinical nurses' emotional experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2021; 30(4):379-389. https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2021.30.4.379

21. Kim N, Yang Y, Ahn J. Nurses' experiences of care for patients in coronavirus disease 2019 infection wards during the early stage of the pandemic. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2022; 34(1):109-121. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2022.34.1.109

24. Noh EY, Chai YJ, Kim HJ, Kim E, Park YH. Nurses' experience with caring for COVID-19 patients in a negative pressure room amid the pandemic situation. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2021; 51(5):585-596. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21148

25. Oh H, Lee NK. A phenomenological study of the lived experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2021; 51(5):561-572. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21112

29. Choi YE, Lee ES. A study on knowledge, attitude, infection management intention & education needs of new respiratory infection disease among nurses who unexperienced NRID (SARS & MERS). Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial cooperation Society. 2019; 20(2):721-731. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2019.20.2.721

30. Oh H, Lee NK. A phenomenological study of the lived experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2021; 51(5):561-572. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21112

33. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. OECD health statistics 2021 [internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2021. [cited 2022 Dec 6]. Available from: http://www. mohw.go.kr

34. Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korean Statistical Information Service [internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2022. [cited 2022 Dec 6]. Available from: http://www.Kosis.kr

Appendices

Appendix 1

PRISMA Checklist

|

Section and Topic |

Item # |

Checklist item |

Location where item is reported |

|

TITLE

|

|

Title |

1 |

Identify the report as a systematic review. |

Page 1 |

|

ABSTRACT |

|

Abstract |

2 |

See the PRISMA 2020 for Abstracts checklist. |

Page 1 |

|

INTRODUCTION

|

|

Rationale |

3 |

Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. |

Pages 2~3 |

|

Objectives |

4 |

Provide an explicit statement of the objective (s) or question (s) the review addresses. |

Pages 2~3 |

|

METHODS

|

|

Eligibility criteria |

5 |

Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. |

Page 3 |

|

Information sources |

6 |

Specify all databases, registers, websites, organisations, reference lists and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. |

Page 3~4 |

|

Search strategy |

7 |

Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers and websites, including any filters and limits used. |

Pages 3~4 |

|

Selection process |

8 |

Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. |

Pages 3~5 |

|

Data collection process |

9 |

Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. |

Pages 3~5 |

|

Data items |

10a |

List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g. for all measures, time points, analyses), and if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

10b |

List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g. participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

Study risk of bias assessment |

11 |

Specify the methods used to assess risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool (s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study and whether they worked independently, and if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

Effect measures |

12 |

Specify for each outcome the effect measure (s) (e.g. risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of results. |

Page 7 |

|

Synthesis methods |

13a |

Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g. tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). |

Pages 5~7 |

|

13b |

Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

13c |

Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

13d |

Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice (s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model (s), method (s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package (s) used. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

13e |

Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g. subgroup analysis, meta-regression). |

Pages 5~7 |

|

13f |

Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

Reporting bias assessment |

14 |

Describe any methods used to assess risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). |

Pages 5~7 |

|

Certainty assessment |

15 |

Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. |

Pages 5~7 |

|

RESULTS

|

|

Study selection |

16a |

Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. |

Pages 7~12 |

|

16b |

Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. |

Page 4 |

|

Study characteristics |

17 |

Cite each included study and present its characteristics. |

Pages 6~7 |

|

Risk of bias in studies |

18 |

Present assessments of risk of bias for each included study. |

Page 5

(Appendices 3) |

|

Results of individual studies |

19 |

For all outcomes, present, for each study: (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. |

Pages 8~9

(Tables 1 & 2) |

|

Results of syntheses |

20a |

For each synthesis, briefly summarise the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. |

Pages 8~9

Table 2.

|

|

20b |

Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was done, present for each the summary estimate and its precision (e.g. confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. |

Pages 7~12 |

|

20c |

Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. |

Pages 7~12 |

|

20d |

Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. |

Pages 7~12 |

|

Reporting biases |

21 |

Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. |

Pages 7~12 |

|

Certainty of evidence |

22 |

Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. |

Pages 17~21 |

|

DISCUSSION

|

|

Discussion |

23a |

Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. |

Pages 17~21 |

|

23b |

Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. |

Pages 17~21 |

|

23c |

Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. |

Pages 17~21 |

|

23d |

Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. |

Pages 17~21 |

|

OTHER INFORMATION

|

|

Registration and protocol |

24a |

Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. |

Title Page |

|

24b |

Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. |

Title Page |

|

24c |

Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. |

Title Page |

|

Support |

25 |

Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders |

Title Page |

|

|

or sponsors in the review. |

|

|

Competing interests |

26 |

Declare any competing interests of review authors. |

Title Page |

|

Availability of data, code and other materials |

27 |

Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found: template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. |

Title Page |

Appendix 2

Citations for Studies Included in this Study

1. Kim N, Yang Y, Ahn J. Nurses' experiences of care for patients in coronavirus disease 2019 infection wards during the early stage of the pandemic. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2022;34(1):109-121. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2022.34.1.109

3. Ha BY, Bae YS, Ryu HS, Jeon MK. Experience of nurses in charge of COVID-19 screening at general hospitals in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2022;52(1):66-79. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21166

4. Kim DJ, Cho MY. Korean clinical nurses' emotional experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2021;30(4):379-389. https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2021.30.4.379

6. Noh EY, Chai YJ, Kim HJ, Kim E, Park YH. Nurses' experience with caring for COVID-19 patients in a negative pressure room amid the pandemic situation. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2021;51(5):585-596. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21148

8. Kim K. A phenomenological study on the nurse's COVID-19 patient care experience in the infectious disease hospitals. The Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2021;21(12):2145-2160. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.12.5.151

10. Oh H, Lee NK. A phenomenological study of the lived experience of nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 in Korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2021;51(5):561-572. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21112

11. Lee N, Lee HJ. South Korean nurses' experiences with patient care at a COVID-19 designated hospital: growth after the frontline battle against an infectious disease pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(23):9015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239015

12. Jin D, Lee G. Experiences of nurses at a general hospital in Seoul which is temporarily closed due to COVID-19. The Journal of Korean Academic Society of Nursing Education. 2020;26(4):412-422. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2020.26.4.412

13. Choi K, Lee K. Experience in responding to Covid-19 of nurse manager at a nursing hospital. The Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2020;11(5):1307-1322. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.11.5.94

Appendix 3

Results of Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Research Checklist of the Selected Studies

|

10 questions |

1. Kim et al.(2022) |

2. Chung et al.(2022) |

3. Ha et al.(2022) |

4. Kim et al.(2021) |

5. Lee et al.(2021) |

6. Noh et al.(2011) |

7. Oh et al.(2021) |

8. Kim et al.(2021) |

9. Park et al.(2021) |

10. Oh et al.(2021) |

11. Lee et al.(2020) |

12. Jin et al.(2020) |

13. Choi et al.(2020) |

|

Clear statement of the aims |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Qualitative methodology appropriate |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Research design appropriate |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Recruitment strategy appropriate |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Data collected in a way that addressed the research issue |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

ethical issues been taken into consideration |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Data analysis sufficiently rigorous |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Clear statement of findings |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Valuable is the research |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|