아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구: 통합적 문헌고찰

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to explore needs for discharge education of family caregivers of pediatric patients through an integrated literature review.

Methods

A systematic search was performed using four electronic databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO) guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. Data were extracted, categorized, and analyzed using the thematic analysis method. The quality of each study reviewed was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT).

Results

In total, 10 studies that were published between January 2012 and December 2021 were included. The MMAT quality scores ranged from 60% to 100%. In this review, needs for discharge education were categorized into contents, methods, and materials.

Conclusion

Pediatrics patients’ families wanted to receive clear and standardized discharge education using visual materials. In addition, they wanted to receive education in a separate place, without their children present, and with sufficient time. Thus, for effective discharge education, standardized educational methods should be developed, and visual materials, such as simulations and videos, should be used.

Key words: Child, Education, Family, Nurse, Patient discharge

주요어: 아동, 교육, 가족, 간호사, 환자 퇴원

서 론

1. 연구의 필요성

간호사는 대상자와 그 가족에게 퇴원교육을 제공하는 주된 책임자로, 퇴원 후 가정에서 수행되어야 하는 대상자의 건강관리에 필요한 기술 및 내용을 대상자와 가족에게 교육한다[ 1, 2]. 간호사가 시행하는 양질의 퇴원교육은 의료의 질과 효율성을 반영하는 중요한 지표인 재입원을 예방하는데 효과적일 수 있다[ 3]. 건강보험심사평가원 자료를 분석한 연구결과, 계획하지 않은 재입원율은 전체 재입원의 9.9%였고 이로 인해 의료비로 약 9,990억원이 지출되었다고 보고된 바 있으며, 이를 예방하기 위해서는 양질의 퇴원교육이 필요하다[ 4, 5]. 미국에서는 환자의 퇴원 후 계획하지 않은 재입원을 예방하기 위해 양질의 퇴원교육을 골자로 하는 Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program을 시행하고 있기도 하다[ 6]. 더 나아가 국내외의 선행연구에 따르면 간호사가 시행하는 양질의 퇴원교육은 가정에서 아동의 건강관리에 유의한 영향을 미치는 것으로 확인되었다. 예를 들어, 국내 뇌전증 아동 가족을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 가족이 인식하는 퇴원교육의 질이 높을수록 가정에서 아동의 약물 관리를 더 잘하는 것으로 나타났다[ 7]. 또한, 비만 아동 가족을 대상으로 한 국외의 선행연구[ 8]에서 퇴원 3개월 이후 아동의 혈당 수치를 비교한 결과, 관리와 치료에 대한 전반적인 내용을 간략하게 전달받은 부모의 그룹보다 다학제가 참여한 체계적인 퇴원교육을 받은 부모의 그룹에서 아동의 혈당 수치가 유의하게 낮음이 보고되었다. 이러한 선행연구의 결과는 양질의 퇴원교육이 의료의 질과 퇴원 후 가정에서 시행되는 아동의 건강관리에 중요함을 시사한다. 양질의 퇴원교육은 간호사가 대상자와 가족의 특성, 환경 및 건강관리 기술과 능력을 고려하여 제공할 때 가능해진다[ 2]. 아동과 가족의 퇴원에 대한 개별적인 요구를 알아보기 위해서는 퇴원 준비 및 교육 과정에서 부모의 의견을 경청하고 퇴원 과정에 이들의 참여를 독려해야 한다[ 9, 10]. 이에 따라, 미국에서는 퇴원의 질 향상을 위해 Include, Discuss, Educate, Assess, Listen (IDEAL) 퇴원 준비모델을 개발하였다[ 11]. IDEAL 퇴원 준비모델은 퇴원계획 과정에서 대상자와 가족을 완전하게 포함하고(Include), 가정에서 발생할 수 있는 대상자의 건강 문제를 예방할 수 있도록 퇴원 후 가정에서의 생활, 약물, 주의해야 할 증상, 진단검사 결과와 외래 예약 일정에 대해 대상자 및 가족과 논의하고(Discuss), 대상자와 가족에게 대상자의 건강 상태, 퇴원 과정 및 퇴원 후 치료과정에 대해 교육하며(Educate), 의료진이 교육내용에 대한 대상자와 가족의 이해도를 사정하고 필요할 경우 재교육하고(Assess), 대상자와 가족의 건강 목표, 선호도, 우려 사항을 경청하고 존중할 것(Listen)을 권장하고 있다[ 11]. 그러나, 현재 병원에서 이루어지는 퇴원 준비는 대상자와 가족의 개인적인 능력이나 요구보다는 대상자의 질병 상태와 치료 절차에 중점을 두며 일률적으로 이루어진다[ 12]. 국내외 선행연구들에 따르면 병원에서는 대상자와 가족의 퇴원 준비도, 교육 요구 및 건강관리 능력에 대한 종합적인 고려가 부족한 채로 퇴원을 준비하고 대상자의 요구를 반영하지 않은 획일적인 퇴원교육을 제공하고 있다고 보고된다[ 13– 15]. 이러한 획일적인 교육은 퇴원 후 아동의 가족이 병원으로 하는 문의 전화 횟수의 증가를 야기하고 아동의 계획되지 않은 재입원 등 부정적인 결과를 초래한다[ 14]. 퇴원 후 가정에서 아동의 건강관리를 증진할 수 있는 양질의 퇴원교육을 제공하기 위해서는 퇴원과 관련하여 아동 가족이 원하는 교육에 대한 요구를 면밀하게 살펴보고 이해할 필요가 있다. 의료기술의 발달로 인해 재원일수가 짧아짐에 따라[ 16], 의료진이 병원에서 제공하는 기관절개관 및 중심정맥관 관리, 비위관영양 관리와 같은 케어를 일찍부터 가정에서 가족이 아동에게 제공하게 되었다[ 17]. 더욱이 짧아지는 재원일수에 따라 퇴원을 준비할 수 있는 기간 역시 짧아지고 있어[ 18] 아동의 가족들은 퇴원 후 가정에서 투약, 상처 관리, 변화된 신체적 상태에 따른 영양과 신체적 활동 등을 포함하는 아동의 건강관리를 수행하는 데 어려움을 겪고 있다. 이러한 아동의 건강관리는 아동의 재입원과 같은 의료기관 이용에 영향을 미칠 수 있으며 아동의 건강 관련 삶의 질에도 큰 영향을 미친다[ 19]. 이에 따라 변화하는 의료환경에 따른 아동 가족의 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 탐색할 필요가 있다. 본 연구에서는 변화된 의료환경 내에서 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구를 탐색하기 위해 최근 10년 이내 출판된 문헌을 대상으로 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 확인하고자 한다. 본 연구에서 확인하고자 하는 요구의 주체는 가족으로, 가정에서 아동의 건강관리에 주된 역할을 가족이 하는 경우에 초점을 맞추기 위해 아동의 연령을 13세 미만으로 제한하였다. 신생아의 경우, 퇴원교육 내용 및 요구의 특수성을 고려하여 제외하였다.

선행문헌을 탐색해 본 결과, 국내에서 아동과 그 가족을 대상으로 한 퇴원교육 요구에 관한 고찰 연구가 있었다[ 20]. 그러나 선행연구의 대상자는 근골격계 수술을 받은 아동과 가족으로 제한되어 있어[ 20], 본 연구에서는 아동의 상태에 제한 없이 입원 경험이 있는 모든 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구를 확인하고자 통합적 문헌고찰을 시행하였다. 통합적 문헌고찰 방법은 주어진 주제를 이해하기 위해 다양한 방법론의 연구결과를 합성하여 주제에 대한 종합적인 시각을 제공하는 문헌고찰 방법이다[ 21]. 본 연구에서 탐색하고자 하는 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구는 대상자의 퇴원경험을 통해 주관적으로 나타나는 것으로 양적연구만으로 심도 있게 파악하는 것에는 제한이 있다. 따라서 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구를 알아보기 위하여 질적연구와 양적연구를 모두 살펴보고 분석할 수 있는 통합적 문헌고찰 방법을 이용하여 연구를 시행하였다.

2. 연구목적

본 연구의 목적은 통합적 문헌고찰을 통해 입원 경험이 있는 아동 가족의 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 탐색하는 것이다.

연구방법

1. 연구설계

본 연구는 아동 가족의 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 탐색하기 위한 통합적 문헌고찰 연구이다. 통합적 문헌고찰의 절차는 Whittermore와 Knafl [ 21]이 제시한 5가지 단계인(1) 문제 인식,(2) 문헌 검색 및 선정,(3) 자료평가,(4) 자료분석 및 의미해석,(5) 자료통합을 통한 속성 도출의 순서를 따랐다. 분석한 결과에 대한 보고의 정확성을 위해 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)[ 22] 체크리스트를 따랐다.

2. 문헌 선정기준

1) 선정기준

본 연구의 문헌 선정기준은 PICOTS (Participants, Inter-vention, Comparison, Outcome, Time, Setting)에 따라 정의하였다[ 23]. 연구대상(P)은 ‘생후 1개월 이하인 신생아를 제외한 입원 경험이 있는 13세 미만 아동의 가족’으로 정의하였다. 본 연구는 아동 환자 가족의 퇴원교육 관련 요구를 포괄적으로 조사하기 위해 질적연구, 조사연구 및 중재 연구를 모두 포함하였으며 중재 연구(I)인 경우 ‘퇴원교육 중재’를 시행한 연구를 포함하였다. 연구의 결과(O)로는 ‘아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구‘로 설정하였고 연구가 이루어진 세팅(S)은’병원에서 퇴원교육이 이루어지고 가정으로 퇴원한 경우‘로 정의하였다. 본 연구는 통합적 문헌고찰로 대조군(C)과 결과 변수에 대한 추적 기간(Time)은 설정하지 않았다.

2) 제외기준

선정 과정에서 퇴원교육 내용 및 요구의 특수성을 고려하여 신생아, 정신질환이 있는 아동 가족만을 대상으로 한 연구는 제외하였다. 문헌고찰, 코멘터리, 초록, 연구 프로토콜 형태이거나 전문을 확보할 수 없는 문헌의 경우에도 제외하였다.

3. 문헌검색 및 선정

1) 문헌검색

본 연구에서는 다양한 국가의 문헌을 검색하기 위하여 국외 의학분야 데이터베이스(Pubmed), 유럽 의학 분야 데이터베이스(Embase), 간호 보건 분야 데이터베이스(Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL))를 이용하여 검색을 시행하였다. 추가로 아동 환자 가족의 퇴원교육 요구에 대한 심리적인 측면도 고려하여 심리학 분야 데이터베이스(PsycINFO)도 검색 데이터베이스에 포함하였다.

주요 검색어는 ‘아동’, ‘가족’, ‘퇴원’, ‘교육 프로그램’, ‘요구’의 단어로 설정하였으며 Pubmed는 MeSH 검색어, Embase 는 EMTREE, CINAHL은 CINAHL Headings, PsycINFO는 Thesaurus 구조를 사용하였고, 유의어를 함께 검색하도록 불리언 연산자 AND/OR 및 절단 검색을 적용하였다. 주요 검색식으로 대상자(P)는(child* OR paediatric* OR pediatric* OR child [MeSH Terms] OR pediatrics [MeSH Terms]) AND (caregiver* OR family OR parent OR parents OR caregivers [MeSH Terms] OR family [MeSH Terms] OR parents [MeSH Terms])로, 중재(I)와 결과(O)는(education OR program OR programs OR (education AND need*) OR educational need* OR education need* OR education [MeSH Terms] OR program development [MeSH Terms])로, 세팅(S)은(discharge OR “ discharge to home” OR “ going home” OR patient discharge [MeSH Terms])를 연산자 AND로 연결하여 검색을 시행하였다. 검색 특이도를 높이기 위하여 검색어가 제목과 초록에서 검색되도록 하였다( Appendix 2). 문헌의 출판연도는 2012년 1월 1일부터 2021년 12월 31일까지로 제한하였으며, 언어는 한국어와 영어로 제한하였다.

2) 문헌선정 과정

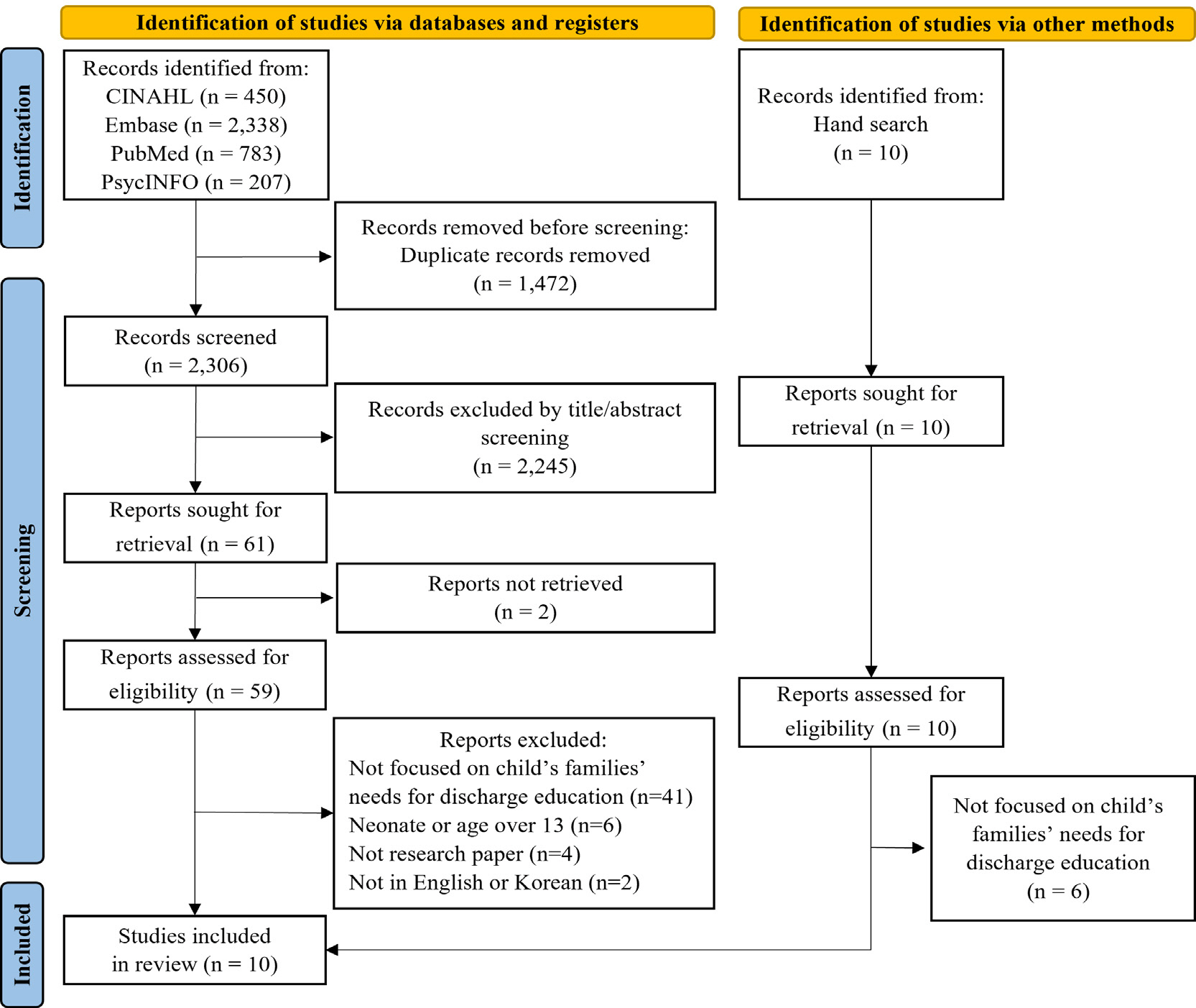

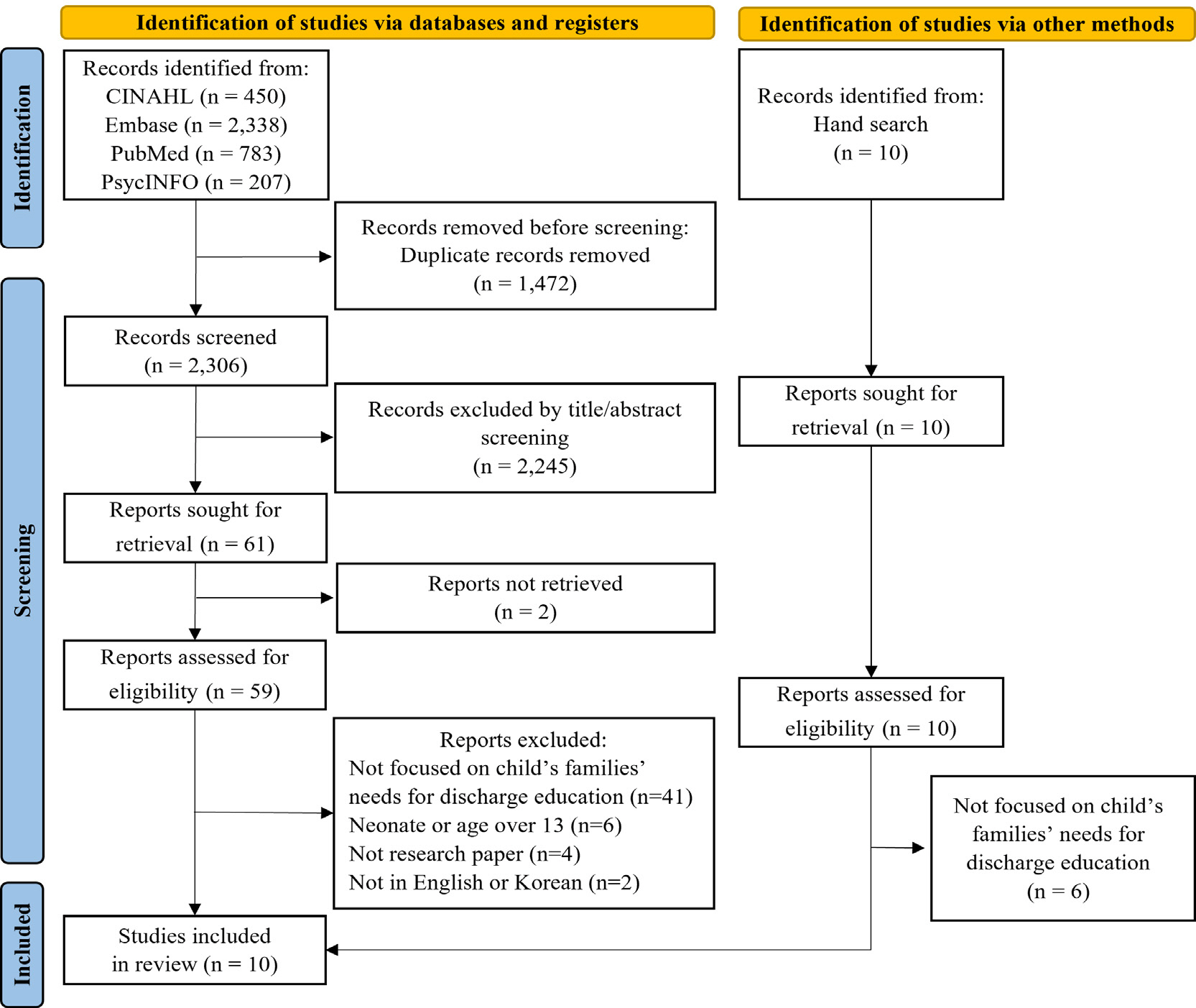

데이터베이스를 통한 문헌검색의 과정은 두 연구자가 함께 진행하였으며, 문헌검색 이후 문헌선정 과정은 두 연구자가 독립적으로 시행하였다. 문헌선정 과정에서 불일치한 의견이 있는 경우 논의를 거쳐 최종 문헌을 선정하였다. 데이터베이스에서 검색된 총 3,778편의 문헌들은 서지 프로그램인 EndNote 에 반입하여 중복문헌 1,472편을 제거하였다. 중복문헌 제거 후 남은 2,306편의 문헌을 두 연구자가 독립적으로 제목 및 초록을 검토하여 통해 본 연구의 선정기준에 부합하지 않은 문헌 2,245편을 제외하였다. 남은 61편의 문헌은 전문 검토를 통해 원문 접근이 불가한 연구 2편, 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구가 나타나지 않은 연구 41편, 적합하지 않은 대상자(예, 성인, 신생아만을 대상으로 한 연구)가 포함된 연구 6편, 배제기준에 포함된 문헌의 형태 4편, 한국어 혹은 영어 이외의 언어로 출판된 문헌 2편을 포함해 총 55편을 제외하여 남은 6편을 분석 문헌으로 선정하였다. 수기로 검색한 10편의 문헌 중 연구 선정기준에 부합하는 4편의 문헌을 추가하여 최종 10편의 문헌을 분석하였다( Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

4. 선정된 논문의 질 평가

최종적으로 선정된 논문의 질을 평가하기 위해 Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT)[ 24]를 이용하였다. MMAT 는 다양한 방법론을 이용한 연구의 질을 평가할 수 있도록 개발된 도구로[ 24], 모든 방법론에 대하여 공통으로 연구 문제와 연구 문제에 따라 수집된 자료의 적절성을 두 항목으로 평가한 후 분석 포함 여부를 결정한다. 이후, 양적연구의 경우 표본 추출의 적절성, 표본의 대표성, 측정 및 통계 분석의 적절성에 따라, 질적연구의 경우 자료수집방법, 결과 분석 및 결과 해석의 적절성과 자료, 수집, 분석 및 해석의 일관성 여부에 따라 연구의 질을 평가한다. 각 항목에 대하여 ‘예’, ‘아니오’, ‘언급할 수 없음’으로 평가할 수 있으며, 본 연구에서는 결과를 합산하여 0%에서 100%까지 변환하였다. 연구자 2인이 선정된 문헌을 MMAT의 각 기준에 따라 독립적으로 평가한 뒤, 의견이 일치하지 않는 경우 논의하여 합의된 의견을 도출하였다. 본 연구에서 선정된 문헌의 MMAT 결과는 100%인 문헌 7편[ 25– 31], 90%인 문헌 1편[ 32], 60% 인 문헌 2편[ 33, 34]이었다( Appendix 3).

5. 자료분석

최종적으로 선정된 문헌의 자료분석은 문헌에서 사용한 연구방법에 따라 문헌 분석표에 다음과 같이 정리하였다. 양적연구의 경우 저자, 출판연도, 연구가 시행된 국가, 연구목적, 연구설계, 아동의 나이 및 특성, 대상자의 수 및 아동과의 관계, 연구가 시행된 장소, 측정변수, 결과로 정리하였으며, 질적연구는 저자, 출판연도, 연구가 시행된 국가, 연구목적, 연구설계 및 분석방법, 아동의 나이 및 특성, 대상자의 수 및 아동과의 관계, 연구가 시행된 장소, 인터뷰 질문, 도출된 주제로 정리하여 분석하였다. 연구자 2인이 독립적으로 문헌 분석표를 정리하고 서로 그 결과를 비교하고 논의하며 문헌 분석표를 작성하였다. 이후, 주제 분석법[ 35]을 사용하여 여러 차례 논의를 거쳐 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구에 대한 주제를 도출하였다.

연구결과

1. 문헌의 일반적인 특성

분석에 포함된 문헌은 총 10편으로 문헌의 특성은 Table 1과 같다. 분석에 포함된 10편의 연구 중 1편을 제외하고 모두 서구문화권에서 이루어졌다. 미국 6편[ 26- 30, 33], 이탈리아 1편[ 31], 캐나다 1편[ 25], 영국 1편[ 34]이었으며, 국내에서 시행된 연구는 1편[ 32]이 있었다. 분석에 포함된 문헌 중 8편의 연구가 질적연구였으며[ 25- 31, 33] 양적연구방법을 사용한 연구가 1편[ 34], 혼합 연구방법을 사용한 연구가 1편[ 32]이었다. 연구대상자 수는 8~171명이었으며 대상자에 포함된 아동 어머니의 수는 8~127명이었고 아동 아버지의 수는 1~44명이었다. 주로 만성질환을 가진 아동의 가족을 대상으로 연구가 이루어졌다. 뇌병증, 근병증과 같이 다양한 영역의 치료가 지속해서 필요하고 심각한 기능 제한을 동반하는 복합 만성질환을 가진 아동의 가족 대상 연구가 5편[ 27- 29, 31, 33], 심장질환을 가진 아동의 가족 대상 연구가 3편[ 30, 32, 34], 중심정맥관을 가진 아동의 가족 대상 연구가 1편[ 26], 혈액 종양을 가진 아동의 가족 대상 연구가 1편[ 25]이었다.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Reviewed Studies (N=10)

|

Authors (year) Country |

Aims |

Design |

Sample |

Child disease characteristics |

Results (Themes) |

|

Bailie et al. (2021) Canada [25] |

To evaluate caregivers' perceptions of a CVC education program to improve education and enhance the provision of safe and competent CVC care at home |

Qualitative |

Stage 1

N parents=9

n mothers=8

n father=1

Stage 2 not mentioned

Stage 3 N

mothers=4 |

Oncology, hematology, bone marrow transplantation |

Themes identified:

-

Stage 1 (evaluation of the CVC education program)

- Demonstration and repeated practice - CVC booklet and video - Fear, stress, and anxiety

Stage 2 (implementing changes to CVC education) -

Stage 3 (evaluation of revised CVC education)

|

|

Callans et al. (2016) USA [26] |

To describe the family experience of caring for their child with a tracheostomy due to a compromised airway during the transition from hospital to home

To identify types of support that families request to be successful caregivers |

Qualitative |

N parents=18

n mothers=16

n fathers=2 |

Tracheostomy status |

Themes identified:

This is not the life I had planned: coming to accept the new reality Don't make the hospital your home: don't make your home a hospital Caregivers engage with providers who demonstrate competence, confidence, attentiveness, and patience Participants value the opportunity to give back and help others

|

|

Canary & Wilkins (2017) USA [33] |

To understand discharge experiences from the perspectives of hospital providers, parents of patients, and outpatient providers |

Qualitative |

N participants=26

n families=11

n primary care providers=15 |

Complex chronic conditions, acute condition |

Themes identified:

Discharge problems Teamwork Ideal discharge Care chasm Discharge paradox

|

|

Desai et al. (2016) USA [27] |

To explore caregiver needs and preferences for achieving high-quality hospital to home transitions in a medically diverse population of pediatric patients |

Qualitative |

N caregivers=18 |

Complex chronic conditions, children with medical complexity |

Themes identified:

Caregiver self-efficacy for home care management Adequate support and resources: from providers, hospital, family and friends, and school Comprehensive knowledge of the care plan: comprehensive discharge education and written discharge instructions

|

|

Gaskin et al.(2016) UK [34] |

To explore parental preparedness for discharge and their experiences of going home with their infant after the first-stage surgery for a functionally univentricular heart |

Quantitative |

N parents=43

n mothers=22

n fathers=21 |

Univentricular heart conditions |

Themes identified in open-ended questions:

Mixed emotions about going home: fear versus excitement Knowledge and preparedness of parents Knowledge and preparedness of community and local hospital teams Support systems

Quantitative results:

Level of understanding of their infant's heart condition at the time of discharge: 27.3% of mothers felt that they ‘understood everything,’ 50% of mothers ‘understood most,’ and only one father felt that he ‘understood everything.’ Quality of discharge information: 50% of the responses rated the quality as good or excellent

|

|

Gold et al. (2020) USA [28] |

To describe parent perspectives and priorities regarding discharge medication education for children with medical complexity |

Qualitative |

N parents=24 |

Children with medical complexity |

Themes identified:

Quality of information, including desire for complete, consistent information in preferred language Information delivery, including education timing before discharge, delivery by experts, and sufficiency of time dedicated Personalization of information, accounting for health literacy of parents and level of information desired Self-efficacy, or the education resulting in the parents' confidence to conduct the medical plan at home

|

|

Lee & Koo (2020) South Korea [32] |

To identify the preferred educational methods and contents among parents caring for infants and toddlers with congestive heart failure after discharge |

Mixed methods |

Quantitative N

parents=171

n mothers=127

n fathers=44

Qualitative

N mothers=8 |

Congestive heart failure |

Themes identified:

Quantitative results:

Parents more wanted to receive education when they had children with acyanotic CHD, received two or more medical interventions, underwent treatment or surgery as a toddler for the first time, were on medication, or had additional treatment or surgery in a schedule 97.1% parents stated that discharge education was needed and the most preferred educational method was direct and offline education The most needed information was symptoms and responses

|

|

Leynaar et al.(2017) USA [29] |

To examine the scope of preferences, priorities, and goals of parents of children with medical complexity regarding planning for hospital-to-home transitions and to ascertain health care providers' perceptions of families' transitional care goals and needs |

Qualitative |

N participants=39

n mothers=19

n fathers=4

n healthcare providers=16 |

Complex chronic conditions |

Themes identified:

Family engagement Respect for families' discharge readiness Care coordination Timely and efficient discharge processes Pain and symptom control Self-efficacy to support recovery and development Social reintegration and establishment of normal routines

|

|

Mannarino et al.(2020) USA [30] |

To identify gaps in caregivers' knowledge and skills regarding the care of their child prior to discharge home from the perspectives of parents and clinicians and assess acceptability of using an educational mobile application as an adjunctive modality for discharge preparation |

Qualitative |

N participants=32

n mothers=22

n fathers=4

n clinicians=6 |

Congenital heart disease |

Themes identified:

-

Caregiver content areas

- Discharge readiness - Caregiver feeling rushed - Gaps in preparedness - Caregiver knowledge with the pre-identified content topics important for discharge - Thoughts on a mobile application for discharge teaching and/or other technology-based support systems

-

Clinician content area

- Questions caregivers commonly ask - Common teaching points - Problems with the discharge process - Thoughts on a mobile application for discharge teaching and/or other technology-based support systems

|

|

Zanello et al.(2015) Italia [31] |

To explore parents' experiences and perceptions on informational, management and relational continuity of care for children with special health care needs from hospitalization to the first months after discharge to the home |

Qualitative |

N parents=23

n mothers=15

n fathers=8 |

Complex chronic conditions |

Themes identified:

|

2. 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구

최종 선정된 문헌에서 도출된 아동 가족의 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 교육내용, 교육방법, 교육자료로 범주화하여 분석하였다. 카테고리에 따른 주제는 다음과 같다. 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육 내용에서는 (1) 명확하고 표준화된 교육과 (2) 질병에 대한 관리뿐 아니라 가정에서 아동을 돌보는데 필요한 포괄적인 정보가 포함된 교육이 주제로 도출되었다. 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육 방법에서는 (1) 아동 가족이 직접 참여하는 교육, (2) 아동 가족의 요구에 맞춘 개별화된 교육과 (3) 충분한 시간 및 독립된 장소가 보장된 교육이 주제로 도출되었다. 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육 자료와 관련한 주제로는 (1) 시각적 교육자료와 (2) 퇴원 후 활용 가능한 교육자료가 도출되었다.

1) 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육 내용

(1) 명확하고 표준화된 교육

분석에 포함된 10편의 연구 중 5편의 연구에서 아동의 가족들은 명확한 퇴원교육 내용과 교육을 제공하는 의료진 개개인의 역량에 따른 편차 없이 전달되는 표준화된 퇴원교육을 원하였다[ 25, 27, 28, 31, 33]. 아동 가족들은 퇴원교육의 내용이 교육을 전달하는 의료진마다 달라 혼란스러웠다고 표현하였다[ 25, 31]. 예를 들어, 가정에서 처음으로 중심정맥관을 관리해야 하는 가족들은 간호사마다 중심정맥관 관리에 대한 자신만의 기법을 퇴원교육 내용에 포함하여 제공하여 퇴원 후 가정에서의 중심정맥관 관리에 혼란을 경험하였다고 이야기하였다[ 25]. 또한, 가족들은 퇴원교육과 함께 제공되는 퇴원 요약지의 내용이 명확하지 않은 경우와 해당 내용을 정확하게 교육받지 못하였을 때 퇴원 요약지가 오히려 가정에서 아동의 건강관리를 방해한다고 말하였다[ 31]. 가족들은 퇴원교육의 표준화와 관련된 요구를 표현하면서 의료진이 표준화된 퇴원교육을 제공할 수 있도록 퇴원 시 구조화된 퇴원 체크리스트를 이용하는 방안을 제안하기도 하였다[ 33].

(2) 질병에 대한 관리뿐 아니라 가정에서 아동을 돌보는데 필요한 포괄적 정보가 포함된 교육

아동 가족은 퇴원교육을 통해 아동의 질병에 대한 관리뿐 아니라 퇴원 후 가정에서 아동을 돌보는데 필요한 다양한 정보를 얻고자 하였다. 가족들이 퇴원교육 내용으로 가장 중요시하는 정보는 아동의 질병 상태 및 질병과 관련하여 주의 깊게 관찰해야 하는 증상과 복용 중인 약물에 관한 내용이었다[ 27, 29, 30, 32, 34]. 수술받은 아동의 경우, 소독법과 같은 수술 부위 관리법에 대한 정보를 원하였으며[ 30, 32], 기관절개관, 중심정맥관 혹은 비위관을 가지고 퇴원하는 아동의 가족들은 가정에서 이를 관리하는 방법에 대해 배우길 원하였다[ 29, 32]. 가족들은 가정에서 발생할 수 있는 응급상황 발생에 대해 큰 우려를 나타내었으며 응급상황 시 대처법과 비상 연락처가 퇴원교육에 포함되어야 함을 강조하기도 하였다[ 27, 32, 34]. 또한, 가족들은 아동의 건강 상태에 따른 적절한 영양, 식사법과 신체적 활동에 관한 내용도 퇴원교육에 포함되기를 원하였으며[ 27, 29, 30, 32, 34], 아동의 심리적 및 신체적 발달 과정에 대한 정보까지도 퇴원교육 내용에 포함되기를 원하였다[ 29].

2) 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육 방법

(1) 아동 가족이 직접 참여하는 교육

가족들은 아동의 퇴원교육에 직접 참여하기를 원하였다. 분석에 포함된 10편의 연구 중 4편의 연구에서 가족들은 가정에서 아동을 돌보는데 필요한 기술을 의료진의 지도로 직접 시행해보고 피드백을 받기를 원하였다[ 25, 27, 30, 31]. 특히, 가정에서 중심정맥관[ 25]을 관리해야 하거나 아동의 건강관리를 위해 의료장비를 사용해야 하는 경우[ 27] 가족들은 가정에서의 아동을 돌보는 것에 대한 자신감을 얻기 위해 퇴원 전 필요한 기술과 장비의 사용법을 직접 익힐 기회가 필수적으로 요구된다고 이야기하였다.

(2) 아동 가족의 요구에 맞춘 개별화된 교육

가족들은 그들의 요구가 반영된 개별화된 퇴원교육을 받기를 원하였다[ 27– 30]. 가족들은 구체적이고 환자 개인에게 맞춰진 개별화된 서면 자료와 이를 활용한 퇴원교육이 병원에서 가정으로의 성공적인 전환 과정에 필수적이라고 이야기하였다[ 29]. 예를 들어, 가족들은 퇴원교육 시, 단순히 복용 약물의 목록 제시만이 아닌 아동의 실제 복용 시간, 빈도, 복용량 및 투여 지침이 퇴원교육에 포함되어야 할 필요가 있다고 하였다[ 27]. 가족들은 그들의 요구에 맞춘 외래 및 검사 일정, 약물 목록과 자신들의 건강정보 이해능력을 고려한 퇴원교육을 원하였다[ 28]. 또한, 가족들은 의료진들이 아동의 발달 정도를 고려하여 가정에서의 건강관리법(예, 약물 복용법 등)에 대해 교육해주길 원하였다[ 30].

(3) 충분한 시간 및 독립된 장소가 보장된 교육

가족들은 퇴원교육을 위한 충분한 교육 시간[ 25, 27, 28, 30, 33]과 독립된 교육 장소[ 27]의 보장을 원하였다. 대다수 가족은 퇴원교육이 퇴원 당일 쫓기듯 빠르게 진행되었다고 이야기하였다[ 25, 27, 28, 30, 33]. 가족들은 퇴원교육 시 의료진이 충분한 시간을 가지고 가족의 교육에 대한 이해도를 확인하면서 가족의 질문에 답해주길 원하였다[ 25, 27, 28, 30, 33]. 가족들은 퇴원 전에 질문할 내용에 대해 생각해보고 질문할 수 있는 시간을 가질 수 있도록 실제 퇴원일 전부터 퇴원교육이 시작되기를 원하였다[ 30]. 가족들은 퇴원교육 시 자신들의 주의가 산만해지는 것을 방지하기 위해, 가능한 아동이 없는 독립된 장소에서 교육받기를 원하였다[ 27].

3) 아동 가족이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육 자료

(1) 시각적 교육자료

아동 가족들은 퇴원 시 비디오와 같은 시각적 자료를 활용하여 교육받기를 원하였다[ 25, 30]. 예를 들어, 아동 가족들은 중심정맥관 관리에 대한 표준지침이 담긴 비디오로 퇴원교육을 제공하는 방법이 효과적일 것이라고 제안하기도 하였다[ 25]. 또한, 가족들은 자신들에게 제공되는 퇴원교육 자료가 가시화되길 원하였다[ 27, 28, 32, 33]. 예를 들어, 가족들은 서면으로 퇴원교육이 제공되는 경우 중요한 내용의 강조를 위해 다른 색으로 표시하는 방법을 사용하는 등의 방법이 필요하다고 하였다[ 27].

(2) 가정에서도 활용 가능한 교육자료

아동 가족들은 퇴원 후 가정에서 아동의 건강관리에 대한 어려움을 겪었으며, 5편의 연구에서 퇴원 후 가정에서도 활용 가능한 교육자료의 필요성을 강조하였다[ 25, 27, 31, 32, 34]. 아동 가족들은 구두로 교육을 받는 경우 퇴원 후 모든 내용을 기억할 수 없으므로 필요한 경우에 언제든 사용할 수 있거나, 퇴원 후 다른 의료시설을 이용할 시 케어의 연속성을 위하여 제시할 수 있는 서면으로 된 자료를 원하였다[ 27, 31, 34]. 또한, 가족들은 가정에서 언제든 시청하면서 재학습할 수 있는 동영상 자료를 원하였다[ 25, 32]. 더 나아가, 가족들은 의료진과 입원 기간과 퇴원 후에도 쉽게 의사소통할 수 있는 창구를 제공하고 아동의 건강관리 정보를 퇴원 후 가정에서도 언제든 확인할 수 있도록 모바일 애플리케이션과 같은 매체가 퇴원교육에서 활용될 수 있다고도 하였다[ 30].

논 의

본 연구에서는 아동 가족의 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 알아보기 위해 통합적 문헌고찰을 시행하였다. 본 연구를 통해 가족들이 필요로 하는 퇴원교육의 내용, 방법 및 자료에 대한 다양한 요구를 파악할 수 있었다. 퇴원교육의 내용적 측면에서 가족들은 아동의 질병에 대한 관리뿐 아니라 가정에서 아동을 돌보는데 필요한 포괄적 정보에 대해 명확하고 표준화된 교육을 받길 원하였다. 교육방법으로는 가족이 교육에 직접 참여하며 그들의 요구가 반영된 개별화된 교육을 받기를 원하였다. 또한, 효과적인 퇴원교육이 될 수 있도록 충분한 시간과 독립된 장소의 보장을 원하였다. 더불어 퇴원 후 지속해서 활용 가능한 시각적 교육자료를 원하였다.

본 연구를 통해 아동 가족들은 명확하지 않은 교육내용과 표준화되지 않은 퇴원교육으로 인하여 퇴원 후 아동의 건강관리에 어려움 경험한다는 것을 알 수 있었다. 퇴원교육이 퇴원 후 가정에서 아동의 건강관리에 큰 영향을 미침에도 불구하고, 국내외 선행연구에 따르면 병원에는 표준화된 퇴원교육을 수행할 수 있는 구조화된 표준지침이 부족한 실정이다[ 28, 36]. 선행연구에 따르면 간호사들은 자신들이 행하는 퇴원교육에 대해 자신이 없다고 보고하였으며[ 37], 이들은 교육학적 기법을 이용하기보다는 자기 경험에 기반하여 교육을 제공한다고 하였다[ 38]. 표준화된 교육지침의 부재, 간호사들의 교육에 대한 자신감 결여와 간호사 개인마다 다르게 사용하는 교육방법은 명확하고 표준화된 퇴원교육 제공을 어렵게 할 수 있다. 퇴원 후 아동의 효과적인 건강관리가 가능할 수 있게 하기 위해서는 아동 가족에게 구조화되고 표준화된 퇴원교육이 제공되어야 한다[ 39]. 이러한 퇴원교육을 위해 교육방법에 대한 명확한 지침이 필요하며, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 에서 제시한 가족이 참여하여 퇴원을 준비하고 교육받을 수 있는 의료진 및 대상자와 가족을 위한 IDEAL퇴원 준비 가이드[ 11] 등을 활용할 수 있다. IDEAL 가이드에는 의료진이 퇴원을 위해 준비해야 하는 내용에 대한 체크리스트와 교육내용을 전달하는 방법에 대한 표준지침, 대상자가 퇴원교육을 통해 알아야 하는 내용과 퇴원교육 내용에 대해 제대로 이해하지 못하였을 시 의료진에게 질문할 수 있는 내용이 포함되어 있다. 이를 통해 의료진은 준비해야 할 퇴원교육 내용과 이를 적절하게 전달하는 방법에 대해 알 수 있고, 대상자와 가족은 퇴원교육을 통해 알아야 할 내용을 숙지할 수 있다. 국내에서도 양질의 퇴원교육을 위해 의료진과 대상자와 가족 모두를 위한 퇴원교육 내용과 전달 방법에 대한 표준화된 지침의 마련이 필요하다. 아동 가족들은 가정에서 아동의 건강관리를 위한 기술들을 직접 시행해보고 이에 대해 의료진에게 피드백을 받는 일련의 교육 과정을 통해 아동의 건강관리에 대한 자신감을 얻은 후 퇴원하길 원하였다. 가족들을 퇴원교육에 직접 참여시키기 위해 시뮬레이션을 활용한 교육방법이 활용되고 있으며[ 40– 42], 이를 통해 가족들은 가정에서 아동을 돌보는데 필요한 기술들을 직접 경험하고 수행할 기회를 가질 수 있다[ 41]. 특히, 비위관, 기관절개관 혹은 중심정맥관을 가지고 퇴원하는 아동들의 가족들은 아동의 건강에 매우 중요한 관리법을 숙지하고 직접 수행하여야 하므로 시뮬레이션 방법이 효과적일 수 있다. 가족을 대상으로 아동의 기관절개관 관리에 대한 시뮬레이션 교육을 적용한 연구에 따르면 시뮬레이션을 활용하여 퇴원교육을 하였을 때, 가족들의 기관절개관 관리에 대한 능력과 자신감이 상승하였고[ 40], 퇴원 후 7일 이내의 재입원율이 감소하였다[ 42]. 이러한 선행연구결과에 근거하여 가족이 비위관, 기관절개관 혹은 중심정맥관 관리법과 같은 아동의 건강에 중요하고 복잡한 기술을 습득해야 하는 경우, 퇴원교육의 효과를 높이기 위해 시뮬레이션을 활용한 퇴원교육을 고려해 볼 수 있을 것이다. 본 연구의 결과, 아동 가족들은 충분한 시간을 가지고 그들의 요구에 따라 퇴원을 준비하고 교육을 받기를 원하였다. 간호사들은 퇴원교육이 퇴원 후 대상자의 건강관리를 위해 중요하다고 인식하고 있지만, 퇴원교육에 할애할 시간이 부족하여 체계적인 교육을 제공하기 어렵다고 하였다[ 20]. 실제로 퇴원교육은 퇴원 당일 대상자의 요구를 파악하지 않은 채 급하게 진행되는 경향이 있었으나[ 30, 43], 제한된 간호 인력으로 퇴원교육에 대한 시간을 늘리기에는 실질적인 한계가 있다. 국외에서는 대상자의 퇴원교육에 대한 이해도를 확인하고 다른 의료진과의 협력을 통해 양질의 퇴원간호를 제공할 수 있는 “퇴원 코디네이터(discharge coordinator)” 제도를 활용하고 있다[ 43]. 퇴원 코디네이터 제도와 관련한 선행연구에 따르면 퇴원 코디네이터 제도 도입 후 병원으로 오는 퇴원 후 문의 전화의 수가 감소하고[ 44], 아동 가족의 퇴원에 대한 만족도가 상승하였으며[ 43, 44], 아동의 재원 기간이 평균적으로 1일 감소하는 결과를 보였다[ 44]. 국내에서도 충분한 시간을 가지고 개별화된 교육을 받기를 원하는 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구를 충족시키기 위해서 퇴원 코디네이터와 같은 퇴원간호를 위한 추가인력을 확보하는 방안을 고려할 필요가 있다. 국내에서는 일부 병원에서 외래에서의 환자 교육과 퇴원 후 대상자 교육을 위한 “설명간호사”제도를 도입하여 활용하고 있다[ 45, 46]. 퇴원교육의 질 향상을 위해 설명간호사의 역할을 퇴원교육에 확대하고 이를 활용하여 퇴원간호를 위한 추가인력확보에 대한 근거를 마련하는 것을 제언한다. 본 연구의 결과 아동 가족은 입원 기간뿐만 아니라 퇴원 후 가정에서도 지속적으로 활용 가능한 시각적인 퇴원교육 자료를 원하였다. Tang 등[ 47]의 연구에서는 조혈모세포 이식을 위해 입원한 아동 가족에게 입원 기간동안 중심정맥관 소독법과 약물 투여 방법에 대해 반복적으로 시청할 수 있는 동영상 자료를 제공하였고, 이로 인해 아동 가족의 퇴원 후 아동의 건강관리에 필요한 지식에 대한 준비도가 증진되었다고 보고되었다. Hoek 등[ 48]은 응급실에서 퇴원하는 아동 가족에게 통증과 진통제 사용과 관련한 교육을 위해 가정에서도 시청 가능한 동영상 링크를 제공하였다. 그 결과, 아동이 통증을 호소할 시 가정에서 진통제를 투여하는 횟수가 증가하였고, 아동이 통증으로 인해 병원을 방문하는 횟수가 감소하였다[ 48]. 더 나아가, Saidnejad와 Zore [ 49]은 효율적인 퇴원교육 방법으로 대상자와 가족이 핸드폰이나 컴퓨터를 가지고 있는 경우 시간과 장소에 구애받지 않고 활용할 수 있는 웹이나 모바일을 활용하는 교육방법을 제시하였다. 응급실 내원 후 퇴원하는 경우 퇴원교육 내용을 서면으로 제공할 뿐만 아니라 퇴원 후에도 원하면 얼마든지 핸드폰 혹은 태블릿과 같은 전자기기를 활용하여 관련 교육 영상을 시청하여 퇴원교육 내용을 숙지할 수 있도록 하였다[ 49]. 입원 기간 및 퇴원 후 가정에서 활용할 수 있는 시각적 퇴원자료에 대한 아동 가족의 요구를 충족시키기 위해 동영상, 웹 혹은 모바일 등 다양한 매체를 활용한 퇴원교육을 고려해 볼 수 있겠다. 본 문헌고찰은 다음과 같은 제한점을 가진다. 본 고찰에 포함된 10편의 문헌 중 1편만이 국내 연구였다. 따라서 본 연구의 결과를 국내 아동 가족에게 적용하는 데는 한계가 있을 수 있으며, 국내 의료환경 내에서 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구를 알아보기 위한 연구가 더 활발히 이루어질 필요가 있다. 본 문헌고찰에 포함된 10편의 연구는 모두 대학병원 혹은 3차 병원에서 시행되었다. 퇴원교육은 의료기관의 특성에도 영향을 받을 수 있어 아동이 입원한 의료기관의 유형에 따라 퇴원교육 요구에 차이가 있을 수 있다. 따라서 본 연구의 결과가 모든 유형의 의료기관에 적용되기에는 제한점이 있으며, 기관의 유형, 간호사 대 환자 비율 등과 같은 의료기관의 특성이 퇴원교육 요구에 영향을 미치는지 알아보는 연구가 시행될 필요가 있다. 또한, 본 연구는 아동 가족의 퇴원교육 요구를 전체적으로 파악하기 위해 선정 및 배제기준으로 아동이 가진 질병 혹은 아동의 의학적인 상태를 제한하지 않았다. 하지만 본 연구에 포함된 아동들은 모두 복합적인 만성질환을 가진 아동들로 본 연구결과를 퇴원을 경험한 모든 아동 가족에게 일반화하기는 어려운 제한점이 있다.

결 론

본 고찰에서는 최근 10년간 국내외 아동 가족의 퇴원교육에 대한 요구를 조사한 10편의 선행 문헌분석을 통해 퇴원교육 내용, 방법과 자료에 대한 가족들의 요구를 통합적으로 확인할 수 있었다. 본 연구의 결과, 아동 가족은 퇴원 후 가정에서의 아동을 돌보는 데 필요한 다양한 정보가 포함된 시각적 자료를 원하였고, 명확하고 표준화된 퇴원교육을 받기를 원하였다. 또한, 충분한 시간을 가지고 독립된 장소에서 가족들이 직접 참여하는 퇴원교육을 원하였다. 이를 기반으로 가정에서 아동의 건강관리를 증진시키기 위한 퇴원교육의 발전 방향에 대해 다음과 같은 제언을 하고자 한다. 첫째, 표준화된 퇴원교육 지침의 마련이 필요하다. 둘째, 아동 가족이 가정에서 아동의 건강관리에 필요한 기술을 습득할 수 있도록 시뮬레이션을 활용한 퇴원교육 방법을 제언한다. 셋째, 아동 가족에게 충분한 시간을 가지고 개별화된 교육 제공을 위해 설명간호사 제도의 확대 적용 및 관련 연구를 제안한다. 마지막으로, 퇴원 후 아동 가족이 필요할 때 활용할 수 있는 동영상 자료를 포함한 웹 혹은 모바일 기반 퇴원교육 매체의 개발 및 이의 효과성을 평가하는 추후 연구를 제언한다.

REFERENCES

1. Weiss ME, Bobay KL, Bahr SJ, Costa L, Hughes RG, Holland DE. A model for hospital discharge preparation from case management to care transition. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2015; 45(12):606-614. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000273

2. Weiss ME, Sawin KJ, Gralton K, Johnson N, Klingbeil C, Lerret S, et al. Discharge teaching, readiness for discharge, and post- discharge outcomes in parents of hospitalized children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2017; 34: 58-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.12.021

3. Green J, Fowler C, Petty J, Whiting L. The transition home of extremely premature babies: an integrative review. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 2021; 27(1):26-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2020.09.011

4. Lee HY, Shin JY, Lee SA, Ju YJ, Park EC. The 30-day unplanned readmission rate and hospital volume: a national population- based study in South Korea. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2019; 31(10):768-773. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzz044

7. Lee HJ, Choi EK, Kim HS, Kang HC. Medication self-management and the quality of discharge education among parents of children with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2019; 94: 14-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.12.030

13. Lee ES, Shin ES, Hwang SY, Chae MJ, Jeong MH. Effects of tail-ored supportive education on physical, emotional status and quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2013; 25(1):62-73. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2013.25.1.62

14. Lee HJ, Soul HA, Lee KN, Seo GO, Moon SM, Kim KH. discharge education reinforcement activities for mother of premature infants. Quality Improvement in Health Care. 2014; 20(1):76-88. https://doi.org/10.14371/QIH.2014.20.1.76

16. Jones SS, Rudin RS, Perry T, Shekelle PG. Health information technology: an updated systematic review with a focus on meaningful use. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014; 160(1):48-54. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1531

17. McCann D, Bull R, Winzenberg T. The daily patterns of time use for parents of children with complex needs: a systematic review. Journal of Child Health Care. 2012; 16(1):26-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493511420186

18. Nowak M, Lee S, Karbach U, Pfaff H, Gross SE. Short length of stay and the discharge process: preparing breast cancer patients appropriately. Patient Education and Counseling. 2019; 102(12):2318-2324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.08.012

22. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petti-crew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015; 4(1):1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

23. Samson D, Schoelles K. Chapter 2: developing the topic and structuring systematic reviews of medical tests: utility of PICOTS, analytic framework, decision tress, and other framework [Internet]. Rockville: AHRQ; 2012. [cited 2022 December 21] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK98235/

24. Hong QN, Fabregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information. 2018; 34(4):285-291. https://doi.org/10.3233/efi-180221

26. Callans KM, Bleiler C, Flanagan J, Carroll DL. The transitional experience of family caring for their child with a tracheostomy. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2016; 31(4):397-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.002

27. Desai AD, Durkin LK, Jacob-Files EA, Mangione-Smith R. Caregiver perceptions of hospital to home transitions according to medical complexity: a qualitative study. Academic Pediatrics. 2016; 16(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.003

28. Gold JM, Chadwick W, Gustafson M, Valenzuela Riveros LF, Mello A, Nasr A. Parent perceptions and experiences regarding medication education at time of hospital discharge for children with medical complexity. Hospital Pediatrics. 2020; 10(8):679-686. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0078

30. Mannarino CN, Michelson K, Jackson L, Paquette E, McBride ME. Post-operative discharge education for parent caregivers of children with congenital heart disease: a needs assessment. Cardiology in the Young. 2020; 30(12):1788-1796. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951120002759

33. Canary HE, Wilkins V. Beyond hospital discharge mechanics: managing the discharge paradox and bridging the care chasm. Qualitative Health Research. 2017; 27(8):1225-1235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316679811

34. Gaskin KL, Barron DJ, Daniels A. Parents' preparedness for their infants' discharge following first-stage cardiac surgery: development of a parental early warning tool. Cardiology in the Young. 2016; 26(7):1414-1424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951116001062

35. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017; 16(1): https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

39. Braet A, Weltens C, Sermeus W. Effectiveness of discharge interventions from hospital to home on hospital readmissions: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2016; 14(2):106-173. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2381

40. Prickett K, Deshpande A, Paschal H, Simon D, Hebbar KB. Simulation-based education to improve emergency management skills in caregivers of tracheostomy patients. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2019; 120: 157-161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.01.020

43. Petitgout JM. Implementation and evaluation of a unit-based discharge coordinator to improve the patient discharge experience. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2015; 29(6):509-517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.02.004

44. Busch R, Cady RG. Discharge nurse intervention on a pediatric rehabilitation unit: retrospective chart review to evaluate the does it impact on number of unmet needs during the transition home following neurological injury. Developmental Neuro-rehabilitation. 2021; 24(8):561-568. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518423.2021.1915403

45. Baek K, Ahn Y, Kim N, Kim M. A study on the nurse in charge of education's current status and legal status. The Korean Society of Law and Medicine. 2013; 14(2):261-280.

46. Kim AY. A phenomenological study on the experience of ex-planation nurse duties [master's thesis]. Seoul: Hanyang University; 2022. p. 1-107.

47. Tang S, Landery D, Covington G, Ward J. The use of a video for discharge education for parents after pediatric stem cell transplantation. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nursing. 2019; 36(2):93-102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454218818059

48. Hoek AE, Bouwhuis MG, Haagsma JA, Keyzer-Dekker CMG, Bakker B, Bokhorst EF, et al. Effect of written and video discharge instructions on parental recall of information about an-algesics in children: a pre/post-implementation study. Euro-pean Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021; 28(1):43-49. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000746

49. Saidinejad M, Zorc J. Mobile and web-based education: deliv-ering emergency department discharge and aftercare instructions. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2014; 30(3):211-216. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000097

Appendices

Appendix 1.

List of the Included Studies

A1. Bailie K, Jacques L, Phillips A, Mahon P. Exploring perceptions of education for central venous catheter care at home. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nursing. 2021;38(3):157-165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454221992293

A2. Callans KM, Bleiler C, Flanagan J, Carroll DL. The transitional experience of family caring for their child with a tracheostomy. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2016;31(4):397-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.02.002

A3. Canary HE, Wilkins V. Beyond hospital discharge mechanics: managing the discharge paradox and bridging the care chasm. Qualitative Health Research. 2017;27(8):1225-1235. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316679811

A4. Desai AD, Durkin LK, Jacob-Files EA, Mangione-Smith R. Caregiver perceptions of hospital to home transitions according to medical complexity: a qualitative study. Academic Pediatrics. 2016;16(2):136-144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2015.08.003

A5. Gaskin KL, Barron DJ, Daniels A. Parents' preparedness for their infants' discharge following first-stage cardiac surgery: development of a parental early warning tool. Cardiology in the Young. 2016;26(7):1414-1424. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951116001062

A6. Gold JM, Chadwick W, Gustafson M, Valenzuela Riveros LF, Mello A, Nasr A. Parent perceptions and experiences regarding medication education at time of hospital discharge for children with medical complexity. Hospital Pediatrics. 2020;10(8):679-686. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0078

A7. Lee BR, Koo HY. Needs for post-hospital education among parents of infants and toddlers with congenital heart disease. Child Health Nursing Research. 2020;26(1):107-120. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2020.26.1.107

A8. Leyenaar JK, O'Brien ER, Leslie LK, Lindenauer PK, Mangione-Smith RM. Families' priorities regarding hospital-tohome transitions for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161581. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1581

A9. Mannarino CN, Michelson K, Jackson L, Paquette E, McBride ME. Post-operative discharge education for parent caregivers of children with congenital heart disease: a needs assessment. Cardiology in the Young. 2020;30(12):1788-1796. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951120002759

A10. Zanello E, Calugi S, Rucci P, Pieri G, Vandini S, Faldella G, et al. Continuity of care in children with special healthcare needs: a qualitative study of family's perspectives. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;41:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-015-0114-x

Appendix 2.

Literature Search Strategy

|

Database |

Search terms |

N |

|

CINAHL |

((TI child* OR TI paediatric* OR TI pediatric*) OR (AB child* OR AB paediatric* OR AB pediatric*) OR (MM ‘pediatrics’) OR (MM ‘child’)) AND ((TI caregiver* OR TI family OR TI parent OR TI parents) OR (AB caregiver* OR AB family OR AB parent OR AB parents) OR (MM ‘caregivers’) OR (MM ‘family’) OR (MM ‘parents’)) AND ((TI discharge OR TI ‘discharge to home’ OR TI ‘going home’) OR (AB discharge OR AB ‘discharge to home’ OR AB ‘going home’) OR (MM ‘patient discharge’)) AND ((TI education OR TI program OR TI programs OR TI education need* OR TI educational need*) OR (AB education OR AB program OR AB programs OR AB education need* OR AB educational need*) OR (TI education AND TI need*) OR (AB education AND AB need*) OR (MM ‘education’) OR (MM ‘program development’)) |

450 |

|

Embase |

((child*:ab,ti OR paediatric*:ab,ti OR pediatric:ab,ti) OR (‘pediatric’/exp OR ‘child’/exp)) AND ((caregiver*:ab,ti OR family:ab,ti OR parent:ab,ti OR parents:ab,ti) OR (‘caregiver’/exp OR ‘family’/exp)) AND ((discharge:ab,ti OR ‘discharge to home’:ab,ti OR ‘going home’:ab,ti) OR (‘hospital discharge’/exp)) AND ((education:ab,ti OR program:ab,ti OR programs:ab,ti) OR (education*:ab,ti AND need*:ab,ti) OR (‘education’/exp)) |

2338 |

|

PubMed |

((child*[Title/Abstract]) OR (paediatric*[Title/Abstract]) OR (pediatric*[Title/Abstract]) OR (child[MeSH Terms]) OR (pediatrics[MeSH Terms])) AND ((caregiver*[Title/Abstract]) OR (family[Title/Abstract]) OR (parent[Title/Abstract]) OR (parents[Title/Abstract]) OR (caregivers[MeSH Terms]) OR (family[MeSH Terms]) OR (parents[MeSH Terms])) AND ((discharge[Title/Abstract]) OR (‘discharge to home’[Title/Abstract]) OR (‘going home’[Title/Abstract]) OR (patient discharge[MeSH Terms])) AND ((education[Title/Abstract]) OR (program[Title/Abstract]) OR (programs[Title/Abstract]) OR (education[Title/Abstract] AND need*[Title/Abstract]) OR (educational need*[Title/Abstract]) OR (education need*[Title/Abstract])OR (education[MeSH Terms]) OR (program development[MeSH Terms])) |

783 |

|

PsycINFO |

(ab (Child* OR paediatric* OR pediatric*) OR ti (child* OR paediatric* OR pediatric*) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘pediatrics’)) AND (ab (caregiver* OR family OR parent OR parents) OR ti (caregiver* OR family OR parent OR parents) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘caregivers’) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘family’) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘parents’)) AND (ab (discharge OR ‘discharge to home’ OR ‘going home’) OR ti (discharge OR ‘discharge to home’ OR ‘going home’) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘hospital discharge’)) AND (ab (education OR program OR programs OR education need* OR educational need*) OR ti (education OR program OR programs OR education need* OR educational need*) OR ab (education AND need*) OR ti (education AND need*) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘program development’) OR MAINSUBJECT.EXACT (‘educational programs’)) |

207 |

Appendix 3.

Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT) in Selected Studies (N=10)

|

First author (year) |

Design |

Methodological quality criteria |

Yes |

No |

Cannot tell |

Comment |

|

Bailie (2021)[25] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Callans (2016)[26] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Canary (2017)[33] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

|

|

✓ |

The analysis method was not described in detail |

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

|

|

✓ |

The themes presented did not sufficiently reflect the child's various disease characteristics because the number of parents of children with acute conditions was much smaller than the number of parents of children with chronic conditions |

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Desai (2016)[27] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Gaskin (2016)[34] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are tdere clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Quantitative descriptive |

4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? |

|

✓ |

|

The demographics of the participants were predominantly well-educated, white, British families |

|

4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? |

|

|

✓ |

Response rate was 35% |

|

4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Gold (2020)[28] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Lee (2020)[32] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Quantitative descriptive |

4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? |

|

✓ |

|

Participants were recruited from one online community where the generalization of the target population cannot be guaranteed |

|

4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Leyenaar (2017)[29] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Mannarino (2020)[30] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Zanello (2015)[31] |

Screening questions (for all types) |

1. Are there clear research questions?

2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

✓

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Qualitative descriptive |

1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation? |

✓ |

|

|

|

Appendix 4.

Summary of Key Findings of Studies Related to the Desire for Discharge Education

|

First author (year) |

Key findings |

|

Bailie (2021) [25] |

Parents stated that guidance, support, and repeated instructions from nurses enabled them to gain confidence in performing the necessary skills of central venous catheter care. Some parents stated that using a booklet for discharge education was helpful, while others stated that booklet needs to be more visualized. Video material was considered as a more visual educational method and the necessity of videos accessible from home was mentioned. Different ways of teaching by nurses led to confusion for the parents, and therefore, they wanted nurses to follow identical guidelines and use the same teaching strategies. |

|

Callans (2016) [26] |

Participants stated that attentive and confident nurses enabled families to become more confident and gain the ability to engage in the caregiver's role more easily. Participants wanted to take part in their child's care and share the role with other family members. Participants also stated that educators who are competent, attentive, and willing to listen can enhance trust with families. |

|

Canary (2017) [33] |

Both families of children and healthcare providers emphasized the importance of preparing discharge from admission to improve the discharge process. Participants of the study recommended utilizing two communication tools for preparing the discharge process (discharge checklist and discharge readiness assessment tool). Participants wanted to have time for answering questions that arise during the discharge process. They wanted clear discharge materials with bullet-points, and a clear follow-up plan. |

|

Desai (2016) [27] |

Caregivers stated that comprehensive discharge education and written discharge instructions are necessary for them to be more prepared and confident for home care management. Caregivers wanted the discharge education to be given from the healthcare providers who are familiar with the child and in a separate place where the child is not present to avoid distractions. Families needed additional time to ask questions and practice the skills needed in caring for their children at home. Caregivers mentioned that education should include an expected overview of the child's recovery period, symptoms to monitor, feeding, hydration, sleep issues, pain control, medication, appointment lists, contact number of the hospital, and wound care. Caregivers also expressed anxiety about the emergency situations and emphasized the inclusion of information in emergency cases, such as emergency contact details and clear instructions for emergency situations, and wanted these to be highlighted for easy access. |

|

Gaskin (2016) [34] |

Parents stated that they could have prepared for discharge more effectively if information about feeding, weight, medication administration, signs of clinical deterioration, risks of normal childhood illness, and emergency contact details were included. At discharge, parents desired comprehensive verbal and written details of discharge, but after discharge, parents wanted contact details of health professionals to ask about the infant's cardiac condition. |

|

Gold (2020) [28] |

Parents felt that education was provided in a fast-paced manner but they needed sufficient time to prepare before leaving the hospital. Parents needed time to understand the instructions given by healthcare providers. Parents desired discharge instructions to include comprehensive, clear, and consistent information with follow-up schedules. Additionally, they desired the use of graphics and instructions in their language, especially the information about medications. Parents wanted education to be provided by experts in the medical field like registered nurses. |

|

Lee (2020) [32] |

Qualitative Families expressed the need for reliable, accessible, and easy-to-understand information using visualized material. Families wanted discharge education to include general information such as feeding, nutrition, development, and physical activity. Furthermore, families desired education related to congenital heart disease (CHD) including general aspects and prognosis of CHD, medical device use, surgical wound management, and responses for emergency situations. |

|

Quantitative Families expressed the need for reliable, accessible, and easy-to-understand information using visual materials. They wanted discharge education to include general information such as feeding, nutrition, development, and physical activity. Families also desired education related to CHD including general aspects and prognosis of CHD, medical device use, surgical wound management, and responses for emergency situations. Parents' educational needs were higher when they had children with acyanotic CHD (p=.019), received two or more medical interventions (p=.001), underwent treatment or surgery as a toddler for the first time (p=.010), were on medication (p<.001), or had additional treatment or surgery in a schedule (p=.001). Fewer than a quarter (16.4%) of the parents had received education regarding children's disease management after discharge, and half (53.6%) of the parents had access to education from hospital or heart foundation websites. Most of the parents (97.1%) stated that education after discharge is needed and the most preferred method of education was direct and offline education (57.9%). Parents' educational needs for CHD management of children were shown by a score of 3.39±0.39 out of 4. The most needed information category was symptoms and responses (3.51±0.46). |

|

Leynaar (2017)[29] |

Parents wanted to take part in their child's care plan decision. Parents wanted individualized written materials and discharge education and emphasized the importance of including information about the child's emotional and physical development. In addition, parents also emphasized the importance of understanding the skills required to administer feeding, assessing feeding tolerance, and managing medical equipment before transition. |

|

Mannarino (2020)[30] |

Caregivers wanted educators to give individualized education including age-specific mobility issues considering the child's condition after surgery. Caregivers desired discharge education to be given earlier considering caregivers' understanding and wanted educators to answer all the questions that arise before the discharge. Caregivers preferred hands-on training and utilization of visual materials such as handouts and videos for their education. Using a mobile application for supplementing discharge education was also mentioned, and caregivers preferred the use of a mobile application. |

|

Zanello (2015)[31] |

Parents wanted to be involved in establishing their child's care plan by participating in meetings with a family pediatrician and community services. Parents wanted all the contact details of hospitals for the continuity of the child's care after discharge. Parents felt that discharge letters from the hospital helped them to provide detailed information about the child's medical condition and hospitalization history, but became a source of concern if not well explained. |

|

|