Factors Influencing Nurses’ Infection-preventive Behaviors for Emerging Infectious Diseases: A Cross-sectional Study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study investigated the effects of knowledge, risk perception, and nursing professionalism on nurses’ infection-preventive behaviors for emerging infectious diseases (EIDs).

Methods

This cross-sectional study's participants were 204 nurses with at least 3 months of experience caring for patients with EIDs at four government-designated medical institutions in Korea, which were the first to handle cases of EIDs.

Results

The average score for infection-preventive behaviors concerning EIDs was 4.54±0.45 points out of 5.00, and the score for the early response stage for EIDs was the lowest. The factors influencing nurses’ infection preventive behaviors for EIDs were personal protective equipment education, knowledge, and risk perception. Nursing professionalism was identified as a new influencing factor.

Conclusion

To improve nurses’ infection prevention behaviors for EIDs, specific and practical training in protective equipment must be conducted. Increasing nurses’ professional knowledge, strengthening risk perception, and implementing strategic programs to strengthen nursing professionalism are required. Nurses should be instructed and given clear rules on properly utilizing personal protection equipment. Nursing managers and nurses can improve their professionalism by creating a positive organizational culture.

INTRODUCTION

Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) refer to diseases that have recently emerged in a population or have previously existed but are rapidly increasing in incidence or geographic range [1,2]. EIDs are a severe threat to the world and the World Health Organization (WHO) South- East Asia Region [1,2]. EIDs have various transmission channels and are also transmitted through zoonosis [2,3]. Among the various EIDs, the most significant international attention is given to coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Ebola virus disease (EVD), and Zika virus, which have been managed with global cooperation [2,4].

In South Korea, there were several outbreaks of EIDs, novel influenza A (H1N1) in 2009, MERS in 2015, and COVID-19 in 2020, and there were few visitors with Zika virus in 2016. After the MRES epidemic, the Korean government established control systems for infectious diseases [5–7]. The government-designated medical institutions quarantined and treated patients with EIDs among national control systems. They were designated to secure healthcare workers and prevent the transmission of infections related to healthcare-associated and community- acquired infections [8].

The nurses caring for patients with infectious diseases in these government-designated medical institutions must have accurate knowledge, a positive attitude, and follow infection-preventive behaviors at all times [2,3,5]. An interrelation was found among nurses’ infection preventive behaviors, knowledge, attitude, perceived risk, and emotional regulation during outbreaks of EIDs such as MERS and COVID-19[9,10]. The willingness to provide care for patients infected with EVD is correlated with public service beliefs, risk perception, and age [11]. Regarding COVID-19, nurses were more willing to care for infected patients when they had more knowledge and risk premium [12]. Therefore, factors influencing nurses’ preventive behaviors for EIDs and knowledge and risk awareness must be examined.

Professionalism is the ability to perform tasks in a specific area based on extensive knowledge and skills and a professional occupation [13]. During the COVID-19 and MERS outbreaks, studies reported that higher nursing professionalism led to nursing care intention for patients with EIDs [14,15]. However, there are limited studies on how nursing professionalism affects infection-preventive behaviors for EIDs [14,15]. To effectively deal with national disasters such as outbreaks of EIDs, a positive work ethic, and professionalism are essential for the willingness to provide care to patients.

Hence, this study aimed to examine nurses’ infection preventive behaviors while caring for patients in government-designated medical institutions for EIDs, including MERS, COVID-19, and EVD, which are paid particular attention in South Korea [8] and East Asia [1]. We also investigated the effects of knowledge, risk perception, and nursing professionalism on infection-preventive behaviors.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This cross-sectional descriptive research study investigated the effects of knowledge, risk perception, and nursing professionalism on infection-preventive behaviors for EIDs.

2. Data Collection

This study identified one tertiary hospital and three general hospitals designated for infectious diseases that provide government-designated care in Incheon, close to Incheon International Airport, where EIDs were first introduced. The relevant departments were government- designated quarantine care beds, emergency rooms, intensive care units, and general wards, and the participants in the study were nurses with experience in treating patients with COVID-19, MERS, or EVD.

3. Participants

Convenience sampling was used for nurses who under-stood the study's purpose. We excluded new nurses who did not engage in patient care and had less than three months of experience. The data was collected in December 2021. The number of study participants was produced using G*Power version 3.1.9[16]. In multiple regression analysis, the calculation result was based on the medium effect size (0.15), significance level (⍺=.05), statistical power (0.90), and the predictor variable (20). The results showed that the required samples were 191, and considering the 25% dropout cases, 240 study participants were finally recruited. The Google Internet surveys were conducted. Among these, 206 participants responded (85.8%), and two did not complete the questionnaire. Consequently, a total of 204 questionnaires were used for the final analysis.

4. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted after receiving the approval of the G university ethics committee (1044396-202109-HR-195-01). The study participants were informed that their data would remain anonymous and only be used for this study. Moreover, they could stop the survey whenever they wanted with no penalty. They were also informed that they would receive a small reward for participation. We obtained approval for data collection from the nursing head offices of the four medical institutions.

5. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed by the SPSS/WIN 23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY) program. It was identified that the most significant variables were a normal distribution and Two-tailed p values were above .05. The differences in infection preventive behaviors for EIDs depending on the characteristics of study participants and institutions were analyzed by independent t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA). The correlations between the most significant variables and infection preventive behaviors for EIDs were analyzed using Pearson's correlations test. The hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted by entering the variables that exhibited a correlation to verify the influencing factors of infection preventive behaviors for EIDs. Before the hierarchical multiple regression analysis, it was confirmed that there was no multicollinearity among variables, and then the regression model was constructed. The total score for each variable was utilized in the differences in infection preventive behaviors, Pearson's correlation test, and the hierarchical multiple regression analysis.

6. Research Tools

1) Infection preventive behaviors concerning EIDs

Yi and Cha's [17] evaluation tool of EIDs developed for intensive care unit nurses was used. There were a total of 18 questions consisting of early response stage for EIDs (four questions), personal protective equipment (PPE) application guidelines (five questions), and infection control guidelines (eight questions). Each question was measured by a 5-point Likert scale, including “ no conduct at all” as 1 point and “ always conduct” as 5 points. The measured scores were distributed between 16 and 80, and higher scores indicated a higher ability to respond to EIDs. In Yi and Cha's (2021) study, Cronbach's ⍺ was .90; in this study, Cronbach's ⍺ was .88.

2) Knowledge related to EIDs

This study referred to the study of Kim and Choi [11] for EIDs-related knowledge, supplemented and amended by referring to EIDs-related instructions provided by the World Health Organization [1]. Among EIDs, MERS and COVID-19, which had spread across Korea, and one merging infectious disease, EVD, which could be introduced in Korea, were selected. A total of 17 questions were measured for scores based on the definition, etiology, mode of transmission mechanism, symptom, treatment, and infection control guideline. The developed questions were verified by three infection control nurse specialists and a nursing professor for the content validity index (CVI), and the final professional CVI was .95. The correct answer was one point, and the wrong answer was zero. A higher score indicated that the participants had better knowledge of EIDs. In this study, the tool's reliability using Kuder- Richardson 20 was .61.

3) Risk perception for EIDs

Regarding risk perception for EIDs, the tool used by Yi and Cha [17] was used. This had four options, including “ EIDs are more critical than any other diseases,” “ EIDs are one of the most critical diseases,” “ One is likely to die if infected with EIDs,” and “ EIDs are a serious threat that can lead to death.” Based on a 5-point Likert scale, “ Strongly disagree” was one point, and “ Strongly agree” was five points. The minimum score was 4, and the maximum score was 20. The higher scores indicated it was more seriously perceived. In Yi and Cha's [17] study, Cronbach's ⍺ was .84; in this study, Cronbach's ⍺ was .85.

4) Nursing professionalism

Regarding nursing professionalism, Hall's Professional Inventory, which was developed by Hall [13] and modified by Snizek [18], was translated into Korean for nurses and used as a standardized tool to verify reliability and validity [19]. There were a total of 25 questions, including five subcategories: the use of professional organizations as a significant reference, belief in public service, autonomy, a belief in self-regulation, and a sense of calling to the field, and each subcategory had five questions. A five-point Likert scale was used to evaluate each question; “ strongly disagree” was one point, and “ strongly agree” was five points. Measured scores were distributed between 25 and 125. A higher score indicated higher nursing professionalism. In Baek et al.'s [19] study, Cronbach's ⍺ was .82; in this study, it was .74.

RESULTS

1. Differences in Infection Preventive Behaviors for EIDs, Depending on the General Characteristics of the Participants and Institutions

Regarding the participants' general characteristics, the average age was 31.47±7.75, with 92.6% being women (189), 26.5% ≥ charge nurses (54), and an average clinical career of 4.54±0.45 years. Regarding medical institutions, 154 participants (75.5%) were in tertiary hospitals, 190(93.1%) were in medical institutions with dedicated beds for additional infection cases, and 129 (63.2%) were in medical institutions with COVID-19 screening inspection for general hospitalized patients. Regarding experience in dealing with EIDs, 204 participants (81.6%) had experience dealing with COVID-19, 37 (14.8%) with MERS, and nine (3.6%) with Ebola. Moreover, 192 participants (94.1%) had PPE education, and 177 (86.8%) received the EIDs education.

There were statistically significant differences in infection preventive behaviors for EIDs depending on the position (F=7.09, p=.008), degree (t=6.22, p=.002), PPE education (t=11.36, p<.001), and EIDs education (t=15.72, p< .001) (Table 1).

2. Degree of Infection Preventive Behaviors, Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Nursing Professionalism for EIDs

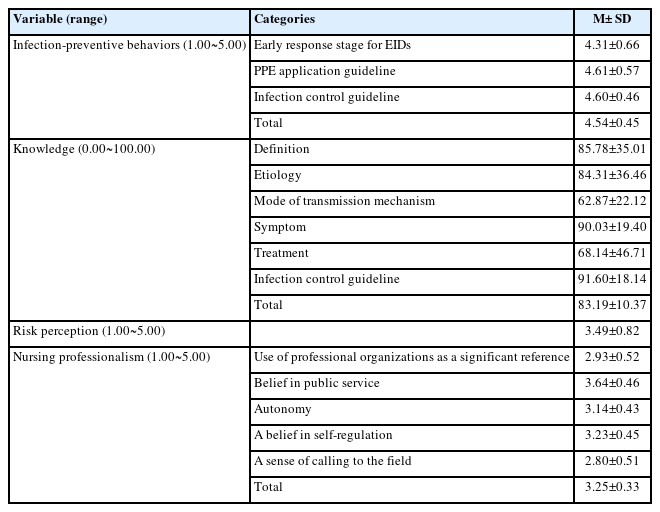

The average score of the infection preventive behaviors concerning EIDs was 4.54±0.45 points out of 5.00, the score of the early response stage for the emerging infectious disease was the lowest, and the score for the PPE application guideline was the highest. The average score of the knowledge related to EIDs was 83.19±10.37 out of 100.00. The mode of transmission mechanism score was the lowest, and the score of the infection control guideline was the highest. The average score of the risk perception on EIDs was 3.49±0.82 out of 5.00. The average score for nursing professionalism was 3.25±0.33 out of 5. In the five subcategories of nursing professionalism, the score of “ use of professional organizations as a significant reference” was the lowest, and the score of “ belief in public service” was the highest (Table 2).

3. Correlation between Independent Variables and Infection Preventive Behaviors for EIDs

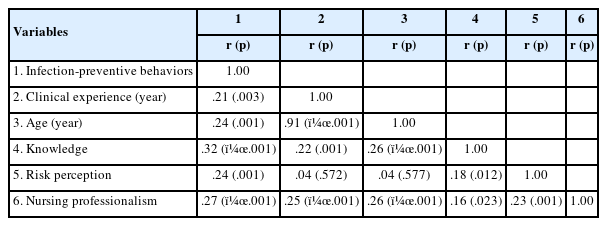

Clinical experience (r=.21, p=.003), age (r=.24, p=.001), knowledge (r=.32, p<.001), risk perception (r=.24, p=.001), and nursing professionalism (r=.27, p<.001) were shown to positively correlate with infection preventive behaviors for EIDs (Table 3).

4. Factors Influencing Infection Preventive Behaviors for EIDs

The Model 1 stage included factors that showed correlations with infection preventive behaviors, such as clinical experience, age, position, degree, PPE education (the training on donning and doffing), and EIDs education. In the Model 2 stage, the knowledge related to EIDs and risk perception was included [5,7,9,10,17]. In the Model 3 stage, nursing professionalism was included in the analysis [14,15].

In the Model 1 stage, the PPE education (β=.17, p=.016) and the EIDs education (β=.18, p=.014) had statistically significant effects with 12.9% of explanatory power.

In the Model 2 stage, the knowledge related to EIDs (β=.23, p <.001) and risk perception (β=.17, p =.009) were included in the PPE education (β=.18, p=.009), and the EIDs education (β=.14, p=.044); these additions had statistically significant effects, and the explanatory power increased to 21.1% by 8.2%.

In the Model 3 stage, nursing professionalism (β=.14, p=.022) was added, and the explanatory power increased to 22.8% by 1.7%. The PPE education (β=.18, p =.006), knowledge related to EIDs (β=.22, p=.001), and risk perception (β=.14, p=.036) had statistically significant effects (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Containing EIDs is a global healthcare concern, and various methods are used to control these by each country [2,4]. The government-designated medical institutions in Korea are where patients with EIDs are hospitalized, and these institutions are at the forefront of controlling infectious diseases and are the first to deal with outbreaks of new EIDs [8]. To effectively respond to patients with EIDs, we must strengthen the infection preventive behaviors of the nurses working in these medical institutions [2,3,9]. This study identified the factors influencing the infection preventive behaviors of nurses caring for patients with EIDs. Notably, this study verified the influence of PPE education [21], the knowledge related to EIDs [5–7], risk perception [9,10,17], and nursing professionalism among nurses.

To cope with EIDs, nurses must perform various professional roles and infection control [21]. Regarding role performance, the training on donning and doffing of PPE and the training related to EIDs were mandatory courses in medical institutions controlling EIDs [8,20]. There were differences in training courses depending on the types of infectious diseases, such as levels C and D, but various healthcare workers were educated according to regular education schedules. However, the training on donning and doffing of PPE requires a relatively more extended period; hence, it is not easy to provide the training repeatedly regularly, and inaccurate training on donning and doffing of PPE can lead to infection in healthcare workers. Healthcare workers employed by government-designated medical institutions were required to be distributed to the field after training in infectious disease and properly fit-ting and removing PPE. Nevertheless, 5.9~13.2% of participants in the study reported they had not received PPE or EIDs education. Therefore, accurate feedback and repeated PPE education are essential [20]. Regarding EIDs such as MERS, COVID-19, and Ebola, appropriate training is required based on the characteristics of the infections and transmission mechanism; precisely, effective education strategy for donning and doffing PPE, such as simulations and demonstrations [22]. Additionally, institutional support is necessary to enable healthcare workers who have completed PPE or EIDs education to engage in caring for patients who have EIDs.

In this study, knowledge related to EIDs and risk perception were the conclusive influencing factors, and Knowledge was the most significant factor. These results indicate that professional knowledge is required for infection-preventive behaviors of emerging diseases. The results align with the prior studies based on various EIDs, including MERS, COVID-19, and Zika [3,5,7,9,10]. Particularly, this study showed that education on the precise transmission mechanism of EIDs is required considering its lack of knowledge. Considering the long-term prevalence of COVID-19, it is reported that a higher knowledge among nurses leads to increased infection control performance. Therefore, professional and repetitive training is required [17].

Risk perception is the degree of perception of the infection. A higher risk perception leads to better infection-preventive behaviors. EIDs are diseases that have recently emerged in a population or threaten humanity. Similar to the prior studies, risk perception significantly influenced infection preventive behaviors [9,10,17]. Therefore, we must strengthen risk perception and knowledge of EIDs; more efforts are required at institutional and national levels.

In this study, nursing professionalism was another factor influencing infection preventive behaviors for EIDs. Nursing professionalism related to EIDs lacked correlation with the study of preventive behaviors. However, it was an influencing factor for willingness to provide care [14]. Regarding EVD, the willingness to provide care correlated with “ belief in public service”, a subcategory of professionalism [11]. However, based on the nurses working for government-designated medical institutions in this study, nursing professionalism did not significantly affect the willingness to care for patients with EIDs [23]. This may be because the prior studies’ participants had less engaging experience and relatively lesser duration in dealing with EIDs. Therefore, nursing professionalism must be considered in specialized and professional nursing, such as nursing for EIDs. The nurses caring for patients with EIDs must have a positive work ethic and perform a professional role [14,15]. In this study, the subcategory of professionalism ranked lowest was “ A sense of calling to the field”, while the top subcategory was “ Belief in public service”. Nursing professionalism received a score of 3.25 ±0.33 points. The nursing professionalism of the study's participants was at a medium level, as shown by the 3.12 ±0.23 points [24] and 3.30±0.45 points [25] nursing professionalism scores in surveys of Korean psychiatric mental health nurses and long-term care hospital nurses.

For each subject, the degree of professionalism subcategory had different outcomes. The Korean psychiatric mental health nurses had the lowest level of “ use of professional organizations as a major reference” and the highest level of “ a belief in self-regulation” [24]. Long-term care hospital nurses, like psychiatric mental health nurses, had the highest “ a belief in self-regulation” and the lowest “ belief in public service”, which is in contrast to this study's findings [25]. The sub-domains of nursing professionalism displayed variations based on the sort of work the nurse performed, whether professional nursing was practiced or not, the type of nursing occupation, and the workplace [13,18,19,24,25]. “ a feeling of calling to the field”, which views work as a calling regardless of pay, was specifically the lowest sub-domain in this study, indicating the need for basic concerns and awareness about the nursing profession.

Regarding infection preventive behavior for EIDs, specific and practical PPE education, a higher knowledge level, and risk perception of the infection are required. Moreover, positive nursing professionalism is required. Specifically, a sense of calling to the field, which had the lowest score in this study, must be improved by actively developing a nursing ethics program and applying it to relevant fields.

1. Limitations

This study investigated limited EIDs, including MERS, COVID-19, and EVD, to which many East Asia countries provide a focus. Extensive investigations on other types of EIDs, which are recently emerging or have a possibility of reinfection, are required in future studies. Moreover, the participants were nurses with experience caring for patients with EIDs at four government-designated medical institutions, and hence, the findings cannot be generalized to all nurses. Future studies must compare results with participants without experience dealing with patients with EIDs. Moreover, additional study participants must be recruited considering various nationalities and cultures.

CONCLUSION

The conclusive influencing factors of infection preventive behavior for EIDs were PPE education, knowledge level, risk perception for EIDs, and nursing Professionalism. Specifically, nursing professionalism was a new influencing factor of preventive behavior for EIDs, and knowledge was the most significant factor. Nurses caring for EIDs require an effective response strategy. Differentiated PPE education depending on the transmission mechanism of EIDs, enhanced professional knowledge, and a public relations strategy that can increase risk perception of the severity of various disease categories are required. Moreover, to improve preventive behavior for EIDs, strategic programs that can strengthen nursing Professionalism and enhance a sense of calling to the field must be developed and applied to relevant areas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank all of the study participants for their participation.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design acquisition - Choi MK and Choi JS; Data collection - Choi MK; Data analysis & Interpretation - Choi MK and Choi JS; Drafting & Revision of the manuscript - Choi JS.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Please contact the corresponding author for data availability.