Infection Control Nurses’ Burnout Experiences in Hospitals during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study was conducted to gain a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of infection control nurses’ burnout experiences in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We recruited 11 infection control nurses (ICNs) who worked in hospitals in Korea through purposive sampling. Data collected through one-to-one, in-depth interviews were transcribed and analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

Infection control nurses’ burnout experiences were categorized into five themes and 11 sub-themes. The themes were as follows: “challenges faced while playing a pivotal role in infectious disease management,” “conflict of interest prevalent inside and outside,” “physical and mental collapse,” “a long road to achieving stability in the infection control unit,” and “source of strength to endure.”

Conclusion

In light of the need to better prepare for future outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, the findings of this study highlight the need for strategic approaches, such as developing programs to provide psychological and social support for infection control nurses, as well as establishing a well-designed system of nursing care for infectious diseases to alleviate their burnout.

INTRODUCTION

1. Background

The 21st century has witnessed the emergence of infectious diseases posing threats to human health, causing fear and uncertainty worldwide [1]. In March 2020, COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), which originated in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [2], was declared a pandemic, the highest level of warning for infectious diseases. The rapid global spread that led to high morbidity and mortality rates worldwide, resulted in significant repercussions in social, economic, educational, and cultural domains [3].

COVID-19 is a highly contagious and potentially fatal respiratory virus, with even asymptomatic cases playing a significant role in spreading it [4]. Thus, healthcare professionals with frequent contact with patients visiting hospitals with suspected symptoms are at a greater risk of infection and transmission and under higher levels of physical and psychological stress than those who are involved in the direct care of patients with COVID-19 [5].

Infection control nurses (ICNs) in hospitals play a pivotal role in preventing infections of other patients, care-givers, and hospital employees from confirmed cases during epidemics by taking measures to block the spread of infectious agents [6]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, these nurses had to adapt to the confusion caused by constantly changing guidelines [7]. Furthermore, they under-took a wide range of duties, such as collecting and reporting COVID-19-related information; developing practical guidelines; making decisions and implementing policies and regulations; providing education/training, advice, and counseling regarding the use of protective equipment, isolation methods, and procedures for hospital employees who contracted the virus; as well as assuming various administrative roles. The increased workload led to higher levels of burnout among these nurses than among general registered nurses [8]. Burnout is a syndrome manifesting three emotional-type symptoms: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment [9]. Emotional exhaustion results from energy depletion owing to excessive work demands, while depersonalization involves adopting a distant and cynical attitude toward patients. Reduced personal accomplishment stems from a negative self-assessment due to a lack of achievement on the job [9]. Burnout leads to physical and mental problems caused by energy depletion and negative emotions at the individual level as well as diminished competitiveness and efficiency that hinder attaining organizational goals at the organizational level [10], which ulti-mately compromises patient safety [8]. Particularly, infection control nurses, who have first hands-on experience of an emerging infectious disease pandemic, as in the case of COVID-19, face even more challenges as they play a pivotal role in the process of coping with it. In this context, exploring infection control nurses’ experiences in-depth is required to provide an understanding on what may cause burnout when dealing with an emerging infectious disease pandemic.

Research on ICNs includes quantitative studies that investigated their core competencies [11], intent to stay [12], and turnover intention [13] along with an empirical study on the benefits of the full-time presence of ICNs in the ICU (intensive care unit) [14], and qualitative studies that described and explored their roles [15], role conflicts [8], and work performance [3]. However, few studies have attempted to explore ICNs experiences of burnout in-depth. Accordingly, a comprehensive description and an in-depth analysis of infection control nurses’ burnout experiences in hospital settings are required to develop pragmatic strategies and intervention methods to offer support and reduce both burnout risks and symptoms.

2. Purpose

This study aims to gain a comprehensive understanding of ICNs burnout experiences in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This is a qualitative study based on the methods of conventional content analysis proposed by Hsieh and Shannon [16], designed for a comprehensive and in-depth exploration of the burnout experiences of ICNs who worked in hospitals’ infection control units during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Participants

ICNs who worked in an infection control unit for at least six months during the COVID-19 pandemic were recruited from four hospitals with a minimum of 200 patient beds in J Province. Purposive and snowball sampling methods were used, to identify participants who wished to actively describe their experiences through recommendations from other people.

Participants were recruited considering appropriateness and sufficiency of qualitative data [17], the sample size of a previous study exploring infection control nurses’ work performance [3], and data saturation. ICNs who vol-untarily expressed their willingness to participate in the study were selected, and data were collected until saturation. Finally, 11 participants were included in the study.

3. Data Collection

Data were collected from June 15 to July 31, 2023. Participants were contacted individually to arrange their de-sired date and time for an interview. Interviews were conducted in quiet locations with restricted access, such as the researchers’ or participants’ offices. To facilitate the in- depth interviews, a semi-structured questionnaire was prepared in advance based on a literature review. The study question was: “ Please share your experiences as an infection-control nurse during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

During the interviews, non-verbal expressions and any noteworthy observations were documented in interview notes. For unclear meanings, follow-up questions were posed for clarity. The researcher conducting the interviews transcribed their content verbatim while repeatedly listening to the recordings. Each participant was interviewed once or twice, with each session lasting from 1 hour to 1 hour and 40 minutes.

4. Data Analysis

We employed Heish and Shannon's conventional content analysis [16] to gain insights into infection control nurses’ burnout experiences. The process began with transcribing the recorded data and comprehending the overall meaning through repeated readings of all transcribed materials. Subsequently, two researchers collaborated to extract meaning units, code the data, and derive sub-themes through an iterative approach. Similar sub-themes were clustered to generate more abstract overarching themes, which were named. Disagreements between the two researchers were resolved through discussions. The interview notes were reviewed during the data analysis.

5. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university (IRB No. KCN 2023-0417-01-1). The participants were briefed on the study's purpose and methods, anonymity and privacy policy in the process, audio recording, as well as their right to withdraw from the study. Furthermore, they were informed that the interview data would be managed under rigorous standards with coding and encryption, and that they would be dis-carded three years (data-retention period required by law) after the study's completion. Accordingly, they signed an informed consent form. As a token of appreciation, the participants were offered a gift after the interviews.

6. Researcher Preparation

All researchers involved in this study have completed courses in qualitative research methodology as part of their graduate studies and published studies related to qualitative research and COVID-19. Additionally, they have diligently kept their knowledge and competence up to date by reviewing relevant literature and texts on qualitative research. They have made conscious efforts to maintain a state of open-mindedness and reflection, striving to avoid biases and preconceptions throughout the research process.

7. Study Rigor

To establish the study's rigor, we followed the criteria proposed by Sandelowski [18], which include credibility, auditability, fittingness, and confirmability. To ensure credibility, we conducted semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions, creating an environment in which the participants could freely present their opinions in a comfortable atmosphere. Additionally, recorded files were carefully reviewed verbatim to minimize omissions or distortions, ensuring that the participants’ words were accurately captured. During the analysis, efforts were made to derive credible results through extensive discussions among researchers. To ensure auditability, we provided detailed descriptions of the data-collection methods and analysis procedures, and the analysis records were verified by two participant nurses to confirm that they matched their experiences and meanings. To ensure fittingness, we offered information about the participants’ general characteristics to allow future studies to apply our findings. We continued data collection until saturation was achieved. Regarding confirmability, we directly quoted participants’ statements within the analysis to enable the verification of the analysis records. Two participant nurses reviewed the analysis results of the interviews and provided feedback, which took approximately 90 minutes each.

RESULTS

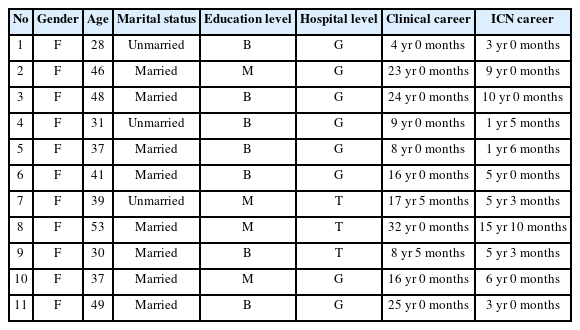

A total of 11 ICNs working at infection control units in one tertiary (three nurses) and three general hospitals (eight nurses) in Province J participated in the study. The participants were women aged 28-53, with a mean age of 39.9 years. The participants’ total clinical careers ranged from 4 to 32 years, while their infection control nursing careers ranged from 1 year and 5 months to 15 years and 10 months (Table 1).

Transcriptions records from the interviews were analyzed through conventional content analysis. A total of 139 meaningful statements were identified, based on which 11 sub-themes and five categories were identified. The final categories of the themes were “ Challenges faced while playing a pivotal role in infectious disease management,” “ Conflict of interest prevalent inside and outside,” “ Physical and mental collapse,” “ A long road to achieving stability in the infection control unit,” and “ Source of strength to endure” (Table 2).

1. Challenges Faced While Playing a Pivotal Role in Infectious Disease Management

Participants’ accounts revealed that the entire hospitals in which they worked relied heavily on the infection control unit for managing emerging infectious diseases during the pandemic, and while they took on the role as the central figures in infectious disease management, they faced numerous challenges. This theme contained the following sub-themes: “ Pressure of decision-making and responsibilities,” “ Overwhelmed by excessive workload,” and “ Confused by unclear job orders.”

1) Pressure of decision-making and responsibilities

Participants found themselves in leadership roles at the front line, overseeing every aspect from setting up screening clinics to their daily operations, and were burdened with numerous decisions and responsibilities. In performing their work while always having to consider and be aware of the overall context, they were faced with the challenges as they were managers of the whole process. They were constantly worried and anxious about whether their decisions made for immediate problem-solving were appropriate in situations where multiple problems had to be simultaneously resolved.

There were matters I could not resolve, and there were also issues that I needed to check and confirm before making decisions; however, all of that became my sole responsibility, and that has been mentally exhausting… quite a lot… (Participant 6)

2) Overwhelmed by excessive workload

Nurses faced a drastic increase in intensive job demands related to COVID-19 in addition to their routine workload. There was no additional staffing to manage such a drastic increase in workload, forcing the participants to work around the clock, even foregoing their days off. They had to take calls 24/7 to respond to the drastic increase in demands for advice and inquiries. They experienced an extreme level of fatigue while dealing with media inquiries and epidemiological investigations. The infection control unit's work procedures tend to be complex, and the rapidly changing government guidelines caused confusion. In this situation, the ICNs had to deal with the complaints made by other hospital staff as they communicated these changes in the guidelines.

Day and night, you know, in the early days, we received inquiries from the local community, public-health centers, provincial offices, and many different hospitals, as well as requests to verify information from reporters from numerous media outlets; there were also inquiries from police offices and all public agencies on everything about how we were dealing with the COVID situation at the hospital I work for and we were the only ones to answer these inquiries or manage requests… (omitted)… I hardly left my desk even on my days off. Even at home, I constantly held onto my phone, answering calls. My phone was with me wherever I went. I just could not be off work, for three years. Even when the public-health emergency was lifted. (Participant 2)

3) Confused by unclear job orders

Subject to the implicit perception within the hospital that all COVID-19-related tasks should be dealt with by ICNs, the participants encountered frequent conflicts with other departments over delegation of duties. They had to bear the responsibility and criticism for the outcomes, and they experienced confusion because of unclear job assignments or orders. These led them to perform tasks outside their nursing duties; accurate information on these tasks was sometimes not properly communicated, further ex-acerbating the confusion.

It is their job, but they would toss it over to us… (omitted)… you know, handing over tasks that other departments could have done. We say that we are really struggling here. We say our workload is extreme, but they insist the task should be performed by us. (Participant 10)

2. Conflict of Interest Prevalent Inside and Outside

In the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, health authorities lacked an organized system for infectious disease management, and public health centers were staffed with inexperienced personnel, with frequent changes in the people responsible. Within hospitals, employees were indifferent to or apprehensive about COVID-19 related tasks. Consequently, participants found themselves in numerous conflicting situations, both internally and externally. This theme comprises the following sub-themes: “ Conflicts with coercive health authorities” and “ Feeling skeptical owing to uncooperative and indifferent attitudes among employees.”

1) Conflicts with coercive health authorities

Faced with a surge in confirmed COVID-19 cases, health authorities rushed to transfer patients to hospitals even when a patient's actual health state had not been properly identified. Moreover, health-authority representatives exerted one-sided pressure, rather than making efforts to communicate and understand the participants’ perspectives to resolve issues pertaining to the management of confirmed cases, which led to conflicts between the hospitals and health authorities. Participants found themselves caught in the middle, and despite their efforts to coordinate opinions, they experienced a sense of skepticism in frustrating situations in which the problems could not be resolved by infection-control nurses.

Strictly speaking, we are not subcontractors of the provincial office. We were cooperating to work together, and we could definitely make it if we collabo-rated… (omitted)… we have limits, but they just insisted and constantly pressurized us… We wanted to do more, but they continued to be coercive. (Participant 1)

2) Feeling skeptical owing to uncooperative and indifferent attitudes among employees

The participants provided guidelines tailored to their respective hospitals in accordance with the frequently changing governmental guidelines for COVID-19 responses, distributing them within their hospitals. However, most hospital employees did not check these guidelines, demanding instant answers instead. Dealing with hospital employees’ uncooperative actions and words whenever they were provided guidelines with which they disagreed, the participants felt a sense of frustration and skepticism. In situations in which difficult decisions needed to be made, ICNs were often used as shields. They had to endure blame and anger for any issue that went wrong, and they were extremely frustrated about not being able to respond emotionally even when treated unjustly.

Even doctors, who are fully capable of making their own decisions in hospitals, wanted us to provide guidelines for everything… (omitted)… And many people seemed to use me as a shield when they knew the guidelines but did not want to follow them. (Participant 7)

3. Physical and Mental Collapse

ICNs working in infection control unit struggled to manage an overwhelming workload, devoting themselves to their duties 24/7 without time to care for their own health. Despite such dedication, the unrelenting, excessive workload took a toll, causing physical, psychological, and emotional distress, and severely affecting the ICNs daily personal lives. This theme encompasses the following sub- themes: “ Physically, psychologically, and mentally overwhelmed and exhausted” and “ Feeling sorry for not being with their families.”

1) Physically, psychologically, and mentally overwhelmed and exhausted

ICNs were responsible for managing confirmed cases of hospital employees; however, when they themselves contracted the virus, they could not afford to rest even during the mandatory isolation period. The persistent, excessive workload led to daily sleep deprivation, headaches, chronic fatigue, lethargy, and depression. Anxiety and fear of having to answer the phone 24/7, sometimes even after work, caused panic attacks. They experienced a continuous state of heightened alertness, even during rest, and had difficulty controlling their emotions, occasionally breaking down in tears unexpectedly when treated un-fairly. They described that they wanted to escape from such situations. Furthermore, they simultaneously felt both the pressure to excel in their roles and inadequate about their own competence, leading to frustration.

You know, when you are tired and exhausted, you need to take a break and refresh yourself, but I just had no such time at first… (omitted)… Whenever someone even approached me, I would burst into tears. I would cry at home too because it just felt so unfair and frustrating. (Participant 11)

2) Feeling sorry for not being with their families

Participants became so engrossed in their COVID-19 duties that they could not attend to their families, growing distant and experiencing conflicts with family members. They projected their negative emotions onto them and were on edge in interactions. Nevertheless, their families tried to be understanding and provide comfort. Participants expressed guilt and remorse for not fulfilling their family roles.

I felt so sorry. I felt sorry because I could not concentrate on anything. I could not concentrate on anything, wherever I went, because I was the mom who was irritable and sensitive. Even for weekends, although I did not go to work in the morning, I would sit and be tapping on this (pointing to the phone) and making calls. Thus, I was a mom who was very… because I would get super sensitive when things did not work out. Therefore, I felt so sorry for that. I was so irritable, and I really felt sorry for that. (Participant 2)

4. A Long Road to Achieving Stability in the Infection Control Unit

Despite the improved level of expertise in infection control measures compared to the situation before the COVID-19 pandemic, the participants expressed concerns about the ongoing inadequacies of the infection control unit in terms of stable and systematic operational measures to manage future infectious disease outbreaks. This theme comprises the following sub-themes: “ Demotivated by lack of recognition for expertise” and “ Work performance falling short of expectations owing to inadequate availability of systematically trained personnel.”

1) Demotivated by lack of recognition for expertise

Since the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, ICNs have performed duties specific to infection control units; however, their expertise has not been adequately recognized, and no compensation was offered for their heavy workload. Particularly, in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the hospital management precluded them from being eligible recipients of government subsidies or paid low-level subsidies on the grounds that they did not provide direct nursing care. The job overload and inadequate compensation increased their intent to change departments or resign. Those who stayed on the job ended up taking on extra work, resulting in night duties and persistent overtime; however, the issue of inadequate compensation was not resolved. Additionally, participants expressed their disappointment and sense of skepticism owing to being alienated even from promotion opportunities, voicing their frustration with remarks that they did not wish to work as ICNs if an emerging infectious disease pandemic arose again.

… (omitted)… I have worked so hard, worked overtime, pouring my heart and soul into it. I have sacrificed my family and suffered from burnout several times. I continued with my dedication despite knowing how mentally and physically exhausted I was. However, if there is no reward for it, then with that experience, if another infectious disease, another event of emerging infectious disease occurred, would I be able to stay here, to do the same things as I did the last time? I cannot answer that. I think I would consider other options. (Participant 10)

2) Work performance falling short of expectations owing to inadequate availability of systematically trained personnel

Participants were assigned to the infection control unit without undergoing systematic training and had to take on central roles in infectious disease management while they were still unfamiliar with their duties. Despite their best efforts to perform, they experienced anxiety from lack of expertise and were dissatisfied with their own work outcomes. The unit experienced a high turnover rate owing to maladjustments to the job; thus, educating and training new staff became another burden for ICNs who stayed on the job. Participants believed that infection control units with structured systems should be established in preparation for the next possible infectious disease outbreak. They emphasized the need for achieving a statutory staffing level with relevant expertise and ongoing education and training tailored to individual hospitals’ needs.

New nurses, that is, nurses who have no infection control unit experience, joined the unit. In fact, there were a few nurses who came here thinking that it would be okay because this is a regular full-time job. Well, this happened in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, when they actually experienced what the job involved, they found “ infection control unit to be way too different compared to other units,” “ There was too much work, and I feel the job is too demanding.” Therefore, many of them left after only a few months. Whenever that happened, we had to take on their work and train new staff, and this was difficult. (Participant 9)

5. Source of Strength to Endure

With the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic, participants felt limited in continuing their duties in the infection control unit and wished to escape. However, they found the strength to persevere with the acknowledgment and encouragement from people who were close to them. As Participants coped with multifaceted challenges, they could learn and grow further, developing their infection-control competencies, thus, building a greater trust in ICNs. This theme encompasses the following sub-themes: “ Enduring with others’ encouragement and support” and “ Developing pride and self-esteem while overcoming challenges.”

1) Enduring through others’ encouragement and support

Although participants had to almost neglect their own families, even having no time to attend to their sick children because of the demanding workload, they received understanding and support from their family members, who provided comfort and encouragement. Participants endured the difficult times owing to the fact that their children were proud of them. In the midst of the shortage in staffing, a strong sense of teamwork and bond developed among infection control unit's team members as they relied on one another; furthermore, the participants could continue because of the support and guidance provided by their unit managers.

We were really close because we spent more time together than with our families. It felt as if we spent more time with the infection control unit's nurses than we did with our family members every day. Thus, we were really close, indeed. I feel as if I could endure all of that because everyone in the unit worked so hard… (Participant 9)

2) Developing pride and self-esteem while overcoming challenges

While striving to solve problems as per rapidly changing government guidelines, participants felt that they developed a broader perspective and thought process. They felt pride, a sense of accomplishment, and increased self- esteem as they realized they could positively contribute to many people and their local communities. Although they remained wary of emerging infectious diseases, they gained confidence in their ability to manage adversity. Despite the challenges, they viewed these experiences as opportunities for growth and developed a stronger sense of responsibility, as this period served as an opportunity to acknowledge the authority of and build trust in infection control nurses.

I have grown considerably more during the pandemic. The infection control unit in which I work has also grown substantially… (omitted)… Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the hospital and employees realized that the infection control unit played a critical role in the hospital… (omitted)… Now, even if another infectious disease breaks out, it will not be as frightening as before, I think, because we can deal with it based on the COVID-19 experience. (Participant 2)

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to understand ICNs burnout experiences in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sub-themes of the first theme, “ Challenges faced while playing a pivotal role in infectious disease management” were “ Pressure of decision-making and responsibilities,” “ Overwhelmed by excessive workload,” and “ Confused by unclear job orders.” Hospitals that had to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic with little systematic preparation came to rely heavily or fully on the infection control unit, causing a range of problems that led to ICNs experiencing excessive workloads and burdens as well as confusion about their duty boundaries. These findings are consistent with other studies’ results [13,15,19], which pointed out that for every outbreak of an emerging infectious disease, ICNs were left to manage a drastic increase in their work, suffering a heavy burden owing to limitations in their competence as infectious disease professionals, and responsibility for their roles. As part of various measures taken to facilitate efficient responses to the infectious disease crisis on a governmental level, Article 46 of the Enforcement Rule of the Medical Service Act stipulated that “ hospital-level medical institutions with not less than 100 patient beds shall establish an infection control unit”[27]; furthermore, more extensive standards were applied on the staffing and placement of healthcare workers related to infection-control, mandating an increase in the required staff [28]. However, in practice, general registered nurses (rather than those with expertise in infection-control) were placed in the unit, resulting in a persistent shortage of healthcare workforce with relevant expertise against the volume of work they faced [3,15]; such a heavy, persistent overload and sense of responsibility led to an increased level of burnout [19]. Therefore, energy depletion became the most direct cause of nurses’ burnout [9].

Additionally, participants experienced “ pressure of decision-making and responsibilities” and “ confusion from unclear job orders.” Owing to a lack of awareness among other hospital staff on the main roles of ICNS, jobs that were not ICNs responsibilities or duties were delegated or passed on, resulting in frequent role conflicts with other units or departments in the hospitals, indicating a control mismatch [9], that is, individual nurses had insufficient control over the resources required to perform their work or insufficient authority to perform the work most effectively. As participants stated in their interviews, performing duties while their responsibility exceeded their authority was highly distressing [9], resulting in their burnout. Therefore, development of a detailed work process for infection control nurses, allocating an appropriate level of roles and authorities, as well as active promotion to improve the awareness of other hospital staff will serve as useful measures to reduce infection control nurses’ burnout.

The second theme, “ Conflict of interest prevalent inside and outside,” had “ Conflicts with coercive health authorities” and “ Feeling skeptical owing to uncooperative and indifferent attitudes among employees” as subcategories. Similar findings were reported in studies, such as frustration from responsive measures lacking consistency, confusion from an absence of communication with community-health centers [3], department-level self-centered-ness with the tendency to deprioritize the work of infection-control, friction between principles and practice, and difficulties in terms of making other departments understand and accept the role of infection control [8]. These findings indicate that being misunderstood in their roles owing to the conflict of interest prevalent both inside and outside led ICNs to experience an interpersonal dimension of burnout in which they showed callous and detached responses in their job [9]. Such an abnormal behavioral state is triggered when people lose a sense of positive connection with their colleagues in the workplace, which in turn leads to individuals’ depersonalization [9]. With increased depersonalization due to communication problems, their interpersonal relationships in the workplace will be further limited [21], reducing work performance and compromising the quality of nursing care [9,30], and even causing problems in patient safety [8]. Therefore, as we predict that humanity will be vulnerable to continuous threats of emerging infectious diseases [20], hospitals should establish a consultative body with local governments to discuss specific measures of cooperation and partnership through communicating and collecting opinions from different perspectives and develop an efficient infection-control system [21].

In the third theme, “ Physical and mental collapse,” the sub-themes were “ Physically, psychologically, and mentally overwhelmed and exhausted” and “ Feeling sorry for not being with the families.” ICNs, typically in a small- staffed infection control unit work setting, not only failed to take care of their own health while taking on physically overwhelming workload, but they also experienced inner anguish and psychological conflicts due to difficulties in work-family balance and feeling sorry and guilty for their families. This finding is similar to those of studies [3,7,8] which reported ICNs experiencing sleep deprivation, headaches, and physical exhaustion from an excessive workload while feeling sorry for family members and anxiety over their possible infection with nurses themselves as the carrier. These findings show that health-related physical and mental symptoms are the results of a prolonged response to chronic stresses from overload, which indicates emotional exhaustion [9]. The results point to the need for an organizational culture as well as psychological and social support in which interventional measures are provided for these physical and mental symptoms reported by ICNs, such as health checkups, stress management, and psychological counseling, which are expected to prevent burnout descending into more severe health problems.

The fourth theme, “ A long road to achieving stability in the infection control unit,” had the sub-themes “ Demotivated by lack of recognition for expertise” and “ Work performance falling short of expectations owing to inadequate availability of systematically trained personnel.” While participants had to take on excessive workloads during the pandemic, they received inadequate compensation that precluded them from being eligible recipients of subsidies or promotion opportunities, thus, leading to them becoming frustrated and demotivated. This finding is consistent with those of studies which reported that ICNs were not respected for their role, were alienated from the reward system, and experienced inadequate compensation [7,8]. Compensation and fairness are key constituents in developing a sense of community through which individuals recognize their values through their work and share a sense of mutual respect [21,31]. As confirmed by this study's findings, when ICNs experience in-adequacy in terms of compensation and fairness related to subsidies and promotions, they become demotivated, feel emotional exhaustion, and develop cynicism toward the workplace, resulting in diminished personal accomplishment [9,21]. Particularly, inadequate compensation and fairness are associated with reduced work efficiency and increased turnover rate [23], as well as increasing burnout from an effort-reward imbalance [24], which even impacts patient safety [8]. Therefore, if work conditions can ensure adequate compensation and fairness, such as reward systems, ICNs can sense their efforts being valued and appreciated, which will contribute to an increased sense of personal accomplishment [23] and serve to prevent them from leaving the infection control unit, thus, reducing the turnover rate.

Additionally, owing to a lack of systematically trained personnel, the ICNs work performance fell short of expectations. Furthermore, despite the fact that work in the infection control unit is highly difficult, relevant training was not provided; consequently, nurses assigned to the infection control unit without training experienced a low level of job satisfaction following inadequate staffing. This finding is consistent with that of a study which reported that ICNs experienced difficulty in adapting to unfamiliar work and an inadequate role assignment owing to career imbalance.

ICNs experience burnout while performing work mis-aligned with their values, and from the mismatch between individual and organizational values regarding their career and expertise. Particularly, duties with high difficulty levels lower nurses’ job performance and self-esteem, resulting in a diminished sense of personal accomplishment [8]. In studies, infection control nurses’ burnout increased when inexperienced nurses with a low level in the infection control core competency joined the infection control unit as new staff [3,8], affecting the ICNs level of job satisfaction and turnover intention [26]. Therefore, to facilitate stable operation and staffing of the infection control unit, it is imperative to establish a strategical plan for human-resource management that considers the experience and qualifications of infection control unit staff and develop a performance-evaluation system with quantitative and qualitative assessments, the results of which could be reflected in their compensation.

Regarding the role of hospitals, an infection control link nurse (ICLN) [29] position, with specific infection control duties, could be established through cooperation between the infection control unit and other departments, as seen in some hospitals abroad. Alternatively, opportunities and support can be provided for ICNs to acquire qualifications as infection control professionals or infection control specialist nurses through systematic training. These measures are also expected to contribute to stable staffing and operation of infection control units.

Finally, the fifth theme, “ Source of strength to endure” comprised the sub-themes “ Enduring through others” encouragement and support” and “ Developing pride and self-esteem while overcoming challenges.” Participants could overcome situations fraught with many challenges owing to the support and encouragement from their families and colleagues; moreover, their pride and self-esteem increased as their professional competence as infection-control nurses gradually improved over the three years of the pandemic.

Furthermore, they developed a heightened sense of duty and responsibility while witnessing a gradual establish-ment of authority and trust in them during the prolonged pandemic period. The findings are similar to those from studies [3,7,13,22] which reported that while performing their infection control duties, ICNs could find positive experiences in the midst of negative ones, such as pressure and helplessness, and overcome challenges with active cooperation and help from other infection control unit members, culminating in a true a sense of accomplishment.

A positive connection with colleagues is achieved through communication, which constitutes social support [9]; social support and teamwork within the workplace are essential factors in emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment [30]. This study showed that, despite an excessive workload and a poor working environment, ICNs managed to overcome burnout through infection control unit members’ group cohesion and support, a sense of duty and responsibility, establishing trust within the hospital over time, and family support.

The interventional measures identified in this study are expected to contribute to preventing infection control nurses’ burnout under stressful situations, such as an emerging infectious disease pandemic, and to further ensuring the safety of the public in Korea beyond the patient-safety level required in infectious diseases.

CONCLUSION

This qualitative study was conducted to gain a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of infection control nurses’ burnout experiences in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic based on Heish and Shannon's [16] conventional content-analysis method. The analysis revealed five prevalent themes on ICNs burnout experiences. Those working in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic period played a pivotal role in infectious disease management and experienced an unrelenting, excessive workload. They had to cope with the burden of decision-making and experienced confusion from unclear duty boundaries.

Furthermore, they faced external challenges in the form of coercive health authorities, which added to their pressure, inner anguish, feelings of skepticism, and frustration due to uncooperative and indifferent attitudes among hospital employees. As such stressful and challenging situations persisted over a prolonged period, the ICNs faced physical, psychological, and mental exhaustion and collapse while feeling sorry for not being able to spend more time with their families. Despite their dedication and sacrifice to perform infection-control duties, no adequate compensation was provided, and they felt that there was still a long way to achieving maturity or stability in the infection control unit system. Nevertheless, their families’ and colleagues’ encouragement and support were their source of strength, owing to which they could endure more than three years of the COVID-19 pandemic. As they overcame the challenges and endured burnout, their work performance also improved, and they felt pride and increased self-esteem for their accomplishment.

This study is significant as it provides an in-depth un-derstanding of ICNs burnout experiences in the face of a prolonged, emerging infectious disease (COVID-19) pandemic, and the findings may be utilized as basic reference data for developing interventional measures to reduce ICNs burnout. However, a study limitation is that it only sampled hospital ICNs personal experiences in a single region through one-on-one interviews; therefore, further study may be required to ensure the findings’ generalizability.

Based on this study's findings, we present the following suggestions for future research. First, further studies are required to develop a program of psychosocial support as part of a strategy of interventional measures for burnout among ICNs, implement the developed program, and evaluate its effects. Second, to reduce burnout among ICNs, additional research is required to develop a program that would promote the active implementation of an infection control link system tailored to the healthcare settings of Korea, apply the developed program, and evaluate its effectiveness.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design acquisition - Lee S-J; Data collection - Lee S-J and Park J-Y; Analysis and interpretation of the data - Lee S-J, Kim S-H and Park J-Y; Drafting and critical revision of the manuscript - Lee S-J, KS-H and Park J-Y.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Please contact the corresponding author for data availability. Dataset files are available at (first author).