How Should Intensive Care Unit Nurses Organize End-of-life Care? A Mixed-methods Study

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to explore intensive care unit nurses' perceptions of end-of-life care and to identify strategies for improving patient comfort in the intensive care unit.

Methods

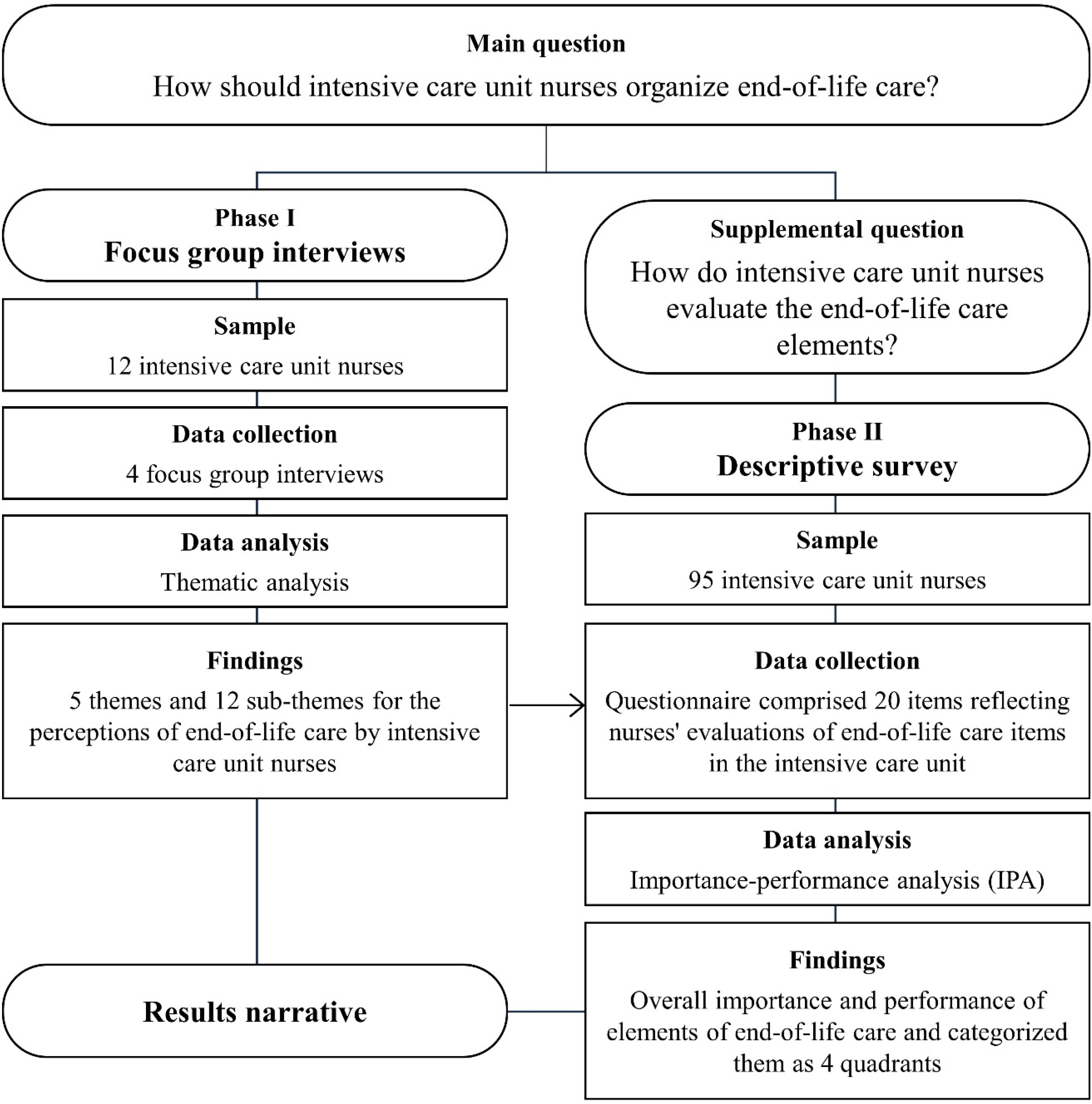

This was a mixed-methods study comprising two phases. In Phase 1, we conducted focus group interviews to investigate how intensive care unit nurses perceived end-of-life care and its specific components within an intensive care unit setting. Phase 2 involved a descriptive questionnaire, utilizing items derived from the focus group interviews to assess how intensive care unit nurses evaluated the components of end-of-life care they provided in the intensive care unit.

Results

The findings of the study's two phases revealed that in end-of-life care, nurses aimed to provide comfort by connecting patients with their families, spiritual beliefs, social networks, and life experiences, while addressing challenges within the broader scope of nursing practice in the intensive care unit.

Conclusion

This study examined intensive care unit nurses' perceptions of end-of-life care, the elements of end-of-life care, their practical implementation, and the associated priorities. These findings will help nurses in intensive care units determine and organize priorities in end-of-life care. For patients facing death in the intensive care unit and for the nurses who care for them, the obstacles involved in end-of-life care must be better overcome.

INTRODUCTION

Critical care has assumed increasing significance within modern hospitals, with intensive care units (ICUs) at the forefront of treating critically ill patients, having adopted progressively more aggressive treatment strategies [1,2]. Nevertheless, a notable number of patients do not recover and pass away within the ICU setting [2,3]. This situation underscores the common occurrence of patients meeting their end in ICUs, where the clinical environment mandates the simultaneous provision of both critical and end- of-life care [1,4].

Within this end-of-life care framework, ICU nurses emerge as the healthcare professionals most intimately ac-quainted with the end-of-life journey, extending their care to encompass not only patients but also their families [5]. Previous research has elucidated that ICU nurses treat patients with dignity, effectively manage physical symptoms, and engage in fruitful communication with patients' families during end-of-life care, which can yield positive outcomes [6–8]. Frequently, the role of an ICU nurse shifts abruptly from providing life-sustaining treatments to the delicate realm of end-of-life care, often involving the with-holding or withdrawal of life-sustaining measures [9,10]. Consequently, ICU nurses grapple with the challenging task of determining the most suitable and feasible approach to end-of-life care within the ICU, leading to substantial stress, uncertainty, ambiguity, and moral distress regarding their identity and role in the care of dying patients [11].

In this context, despite ICU nurses playing a pivotal role in end-of-life care, they face obstacles such as limited participation in end-of-life care decision-making and the dilemma of prioritizing care for end-of-life patients [12]. Unsurprisingly, the domain of end-of-life care has become a focal point of discussion in intensive care settings [13]. While the literature underscores the multifaceted role of ICU nurses, spanning patient, family, and environmental care, it remains unclear how ICU nurses perceive end-of- life care and what priorities they ascribe to it [14,15]. To alleviate the stress and moral distress stemming from in-adequate end-of-life care, it is imperative to provide clarity on the scope of end-of-life care within the realm of ICU nursing. Therefore, this study aimed to explore pragmatic approaches to end-of-life care from the perspectives of ICU nurses and to identify strategies for enhancing patient comfort within the ICU setting.

METHODS

A qualitatively-driven mixed methods study [16] was conducted in two phases (Figure 1). In Phase 1, we employed focus group interviews (FGI) as the primary research method to explore ICU nurses' perceptions of end- of-life care and the specific components of such care within an ICU setting. Phase 2 consisted of a descriptive questionnaire using items derived from the FGI to investigate how ICU nurses evaluated the components of end-of-life care performed by nurses in the ICU. The Consolidated Criteria for Qualitative Research Reporting (COREQ)[17] was used for the structure and organization of this research report.

1. Phase 1: Focus Group Interview (FGI)

1) Participants

For FGI, it is generally accepted that between six and eight participants per group are sufficient [18]. We recruited participants for two groups based on their ICU clinical experience using purposive sampling from a university hospital in Seoul, Korea. Group 1 included six nurses with more than 10 years of experience, while Group 2 comprised six nurses with less than 10 years of experience. This categorization, established during the recruitment process to facilitate group dynamics, ensures participants share sufficient common ground for meaningful discussions [18], recognizing potential variations in perceptions of end-of-life care and its significance based on nurses' lengths of ICU experience [19]. In Group 1, the average age of participants was 38.1 years, and their educational back-grounds consisted of five college graduates and one master's program graduate. Their clinical experience ranged from 11 to 16 years, with an average of 13.25 years. Convertsely, Group 2 participants had an average age of 29 years, and all held college degrees. Their clinical experience spanned from 2 to 8 years, with an average of 4.75 years.

2) Data collection

The FGI was conducted online via Zoom meetings due to COVID-19 infection concerns. Four interviews were conducted, with each group being interviewed twice from December 2022 to February 2023. During the initial FGI, the researchers conducted briefing sessions for each interview question to maintain internal consistency across the two groups. Examples of the interview questions included, ‘How do you define end-of-life care?’, ‘What do you think is the most crucial quality required of ICU nurses performing end-of-life care?’ Subsequently, in the second FGI, participants engaged in a more detailed discussion of their perceptions of end-of-life care. The researchers introduced participants to Kolcaba et al.'s theory of comfort, which identifies the comfort needs of dying patients in physical, psychological, environmental, and sociocultural contexts [20]. Discussions were then conducted to derive the elements of end-of-life care performed by nurses in the ICU. The questions in the second interview covered the four contexts of the theory of comfort, such as ‘Do you have any nursing experience in proving patients’ physical or emotional comfort?’ and ‘What do you think is the nurse's role in spiritual, environmental, and socio-cultural nursing?’ The interview continued until theoret-ical saturation was reached, where a clear pattern of agree-ment among participants emerged, and subsequent questions produced no new information [18]. Each interview lasted for 60 to 90 minutes, was recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

3) Data analysis

The FGI was analyzed using the qualitative thematic analysis method [21]. The researchers familiarized them-selves with the transcriptions by reading them repeatedly and identified meaningful data for generating codes. The initial codes were developed and sorted into potential themes. After identifying these themes, they were reviewed and discussed to identify overarching themes. Further discussions were held until a consensus was reached on naming the identified themes.

4) Trustworthiness

To validate our analysis, we summarized key points for participants at the end of each answer, restating their language to ensure accurate capture of intentions and perspectives during discussions [22]. We also involved a nursing professor and three nursing doctoral students with ICU experience to cross-check coding and theme selection, ensuring consistency.

2. Phase 2: Descriptive Survey

We conducted a descriptive survey to assess the participating nurses' perceptions of the importance of the end-of-life care elements performed by ICU nurses, as well as their evaluations of them. To achieve this, we employed an importance-performance analysis (IPA), which is a method that efficiently identifies priority items among multiple targets without the need for complex statistical techniques [23].

1) Participants and data collection

In this phase, participants were recruited from various ICUs, including medical, surgical, neurologic, cardiovas-cular, and emergency units, at a university hospital in Korea. The inclusion criterion required ICU nurses with more than one year of clinical experience, as they could effectively specify or explain situations [19].

The widely accepted rule of thumb for sample sizes in social science surveys, typically considered adequate for IPA surveys, prescribes a minimum acceptable sample size of 100 surveys [24]. Consequently, between April 17 and April 21, 2023, this study distributed surveys to 104 ICU nurses who willingly participated. The first author visited the ICU to distribute a paper questionnaire, allowing participants to complete it before or after work. The questionnaire took approximately 30 minutes to fill out. After accounting for attrition, a final group of 95 ICU nurses completed the IPA questionnaires. Of these participants, 10 were male and 85 were female, with an average age of 29.57 years (standard deviation: 4.4). Additionally, 56.8% of them had less than 5 years of working experience.

2) Instrument

The instrument for the IPA comprised 20 items reflecting ICU nurses' evaluations of end-of-life care items in the ICU. These items were generated from the FGI while considering the theory of comfort [20]. Each of the 20 items was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree); the items are presented in Table 1.

3) Data analysis

The collected questionnaires were analyzed using SPSS version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The importance and performance awareness regarding the items of end- of-life care in ICUs were analyzed by means and standard deviations. The mean values of importance and performance awareness were used to divide the matrices into four quadrants.

4) Ethical considerations

This study received approval from the hospital's institutional review board (IRB No. 2022GR0493). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after presenting the study's purpose and protocol. Additionally, participants were assured that their privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity would be safeguarded.

Results

1. Phase I: Focus Group Interviews (FGI)

Through this study, 5 themes and 12 sub-themes were derived for the ICU nurse participants’ perceptions of end-of-life care (Table 2). Theme 1 concerns the care of patients' families as a focus of end-of-life care in the ICU, and theme 2 considers the context of end-of-life care in the ICU. Themes 3, 4, and 5 are about how to structure end-of- life care centered on ICUs. Each item in the research instrument of the descriptive study in Phase 2 was derived from Themes 1, 3, 4, and 5.

1) Theme 1: End-of-life care units: Connection with family and patients

The participants often encountered end-of-life care situations in ICUs. Throughout this process, they provided comprehensive end-of-life care that extended to include family members until the patient's passing. Theme 1 includes two sub-themes: supporting the death process together with the patient and family as a unit, and clarification of the situation in the patient-family relationship through the provision of information.

Participants stressed the importance of supporting both patients and their families as a unit to help them come to terms with and endure the inevitability of death. They highlighted the need to actively respond to patients' and families' requests for explanations regarding the patient's condition. In the context of end-of-life care, nurses recognized the importance of arranging interviews with medical staff to ensure that the family is well-informed about the patient's condition as they near the end of life.

2) Theme 2. Combining acute critical care with end-of-life care

Theme 2 considers the obstacles to nurses performing end-of-life care in ICUs. It is composed of two sub-themes: a space where care for patients in the end-of-life phase and critical patients in the acute phase are combined and nursing for the survival of critically ill patients coexisting with dignified death at the end of life.

Participants knew the importance of end-of-life care, but they expressed regret that they could not adequately perform end-of-life care due to their busy workloads and the resulting lack of time. Participants said they thought that patients in the dying process needed assistance in mentally preparing for death and should be respected as dignified human beings but that they were experiencing a great sense of loss from not being able to properly respect human dignity in a field that prioritized providing direct nursing care.

3) Theme 3. Physical care at the boundary between life and death with dignity

Theme 3 focuses on the physical aspects of nursing that nurses can perform in the ICU, where obstacles to end- of-life nursing coexist. Theme 3 has three sub-themes: structuring end-of-life care tailored to the ICU, considering patient's symptoms, emphasizing pain management to enhance quality of life, and maintaining the dignity of dying patients through physical appearance management.

The participants said they provided comprehensive end-of-life care within the ICU that encompassed addressing patients' symptoms and engaging in non-verbal com-munication, such as physical touch. Throughout the end- of-life process, participants prioritized the enhancement of patients' and families' quality of life and the relief of pain over mere treatment objectives. Furthermore, the participants placed significance on how the patient was perceived by their family.

4) Theme 4. Linking spiritual/social/psychological well- being to end-of-life care

Theme 4 concerns the end-of-life care that nurses can provide so that patients in the dying process in the ICU do not feel lonely and afraid. Theme 4 is composed of three sub-themes. They are spiritual connections: letting patients know they are not alone; social connections: encouraging patients to recognize that they have not been forgotten in the social network; and psychological connections: helping patients recognize that the nurse is still focused on what they are saying.

The participants displayed profound empathy for patients' fear of facing death alone and stressed the importance of spiritual care in addressing this fear. They emphasized the crucial role of nurses in providing information related to religion and conducting spiritual nursing through religious rituals. Additionally, the participants recognized the significance of non-family social support systems, which are often unavailable within the confines of a hospital ICU, in a patient's end-of-life journey.

5) Theme 5. Environmental considerations that dying patients deserve

Theme 5 states that while an ICU is where care for patients receiving life-saving treatment and patients being provided end-of-life care coexist, there is a need for an ICU's structural considerations to better include the dying. Theme 5 consists of two sub-themes: providing space and opportunities for organizing and reflecting on a patient's life in the ICU, and consideration that enables patients to have control and make choices during their final days as they approach the end of life.

Participants recognized the importance of creating a peaceful environment for patients, one that provided emotional support to ease their anxiety during the dying process. This support allowed patients to reflect on their lives while ensuring their families’ presence. They also suggested a need for end-of-life care conditions where nurses could respond to evolving patient needs, hopefully preventing lingering regrets about accepting death.

2. Phase II: Descriptive Study

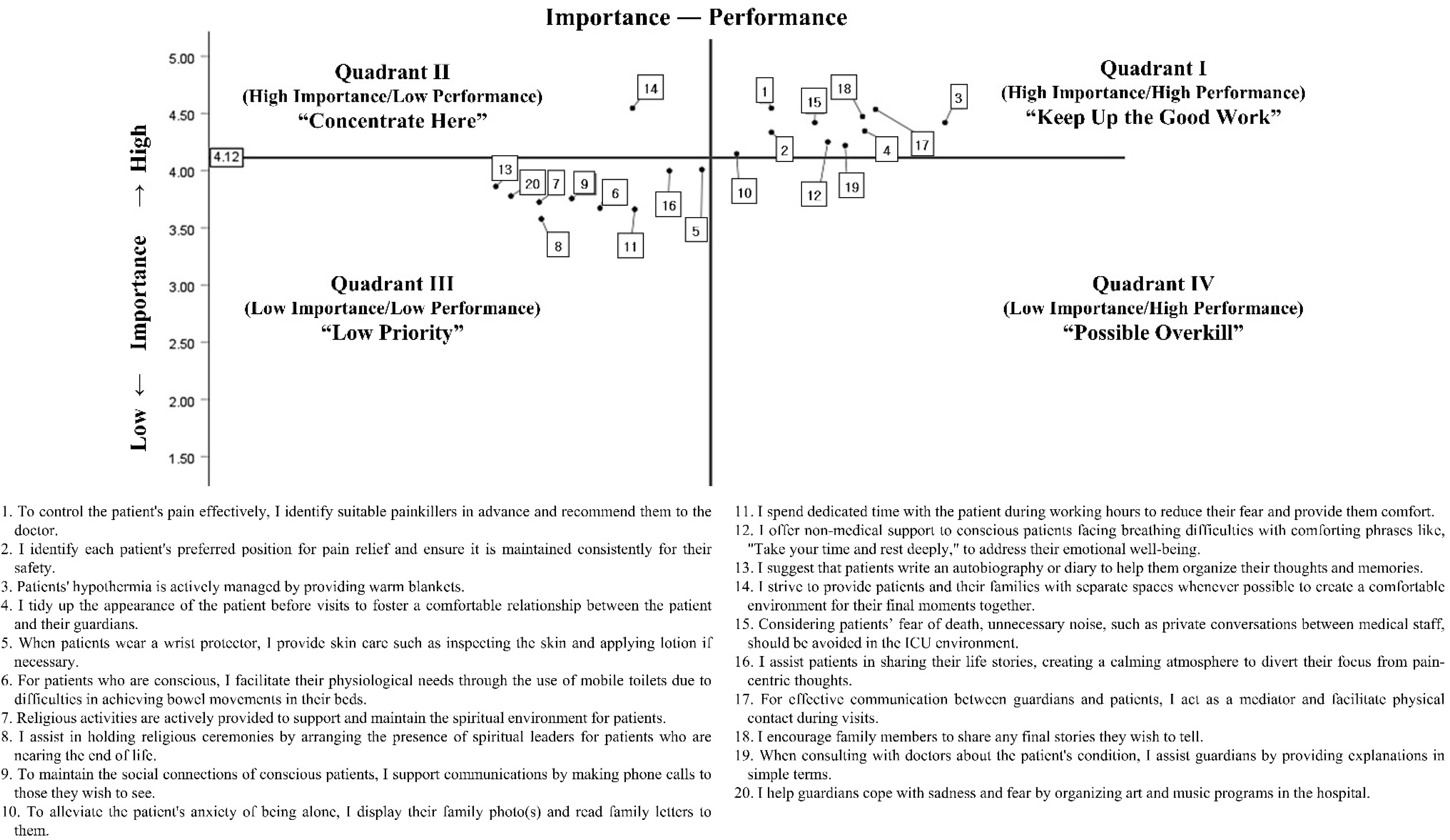

The results of the descriptive study presented an evaluation of the items of end-of-life care performed by nurses in the ICU using an IPA, as shown in Table 1. The overall importance of the elements of end-of-life care in the ICU was rated at 4.12±0.85 (mean± standard deviation), while the overall performance was rated at 3.21±1.17. Figure 2 displays the IPA matrix illustrating the distribution of importance and performance.

In the IPA matrix, 10 items included in Quadrant I (Keep up the good work) are 1, 2, 3, 4, 10, 12, 15, 17, 18, and 19, representing areas for strengthening and maintaining both importance and performance. These were identified as end-of-life care items that must continue to be performed in the future. Additionally, Quadrant II (Concentrate here) is considered important, but its actual performance is low. Therefore, item 14 was identified as a priority for focused improvement. The items included in Quadrant III (Low priority) in the IPA were deemed to possess relatively low importance and performance, and 9 items (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 16, and 20) were included. Because these items have both low importance and low performance, they require more focus. Quadrant IV (Possible overkill) is an area with high performance but relatively low importance, and there were no items included in this Quadrant in the IPA.

1) Results narrative: Nurses' perceptions of end-of-life care in ICUs

Through a qualitative-driven quantitative mixed methods approach, this study's findings reveal that ICU nurses possess a solid understanding of end-of-life care. However, they often encounter confusion as end-of-life care over-laps with the care of critically acute patients.

According to Quadrant II (Concentrate here) of IPA, the need for a dedicated space within the ICU for end-of-life patients and their families emerged as the most urgent element of end-of-life care. ICU nurses evaluated this as crucial, indicating that it's not ideal for patients in the ICU to be cared for in an environment designed for both critically ill patients and those at the end of life. According to Quadrant I, nurses prioritize addressing patients' physical symptoms directly at the bedside as an essential aspect of end- of-life care. However, other aspects, such as spiritual, social, and psychological support were considered lower priorities and included in Quadrant III. On the other hand, there were hardly any items corresponded to Quadrant IV (Possible overkill) among the end-of-life care elements derived from the FGI. This indicates that most ICU nurses recognize these aspects as necessary if the ICU environment supports them.

In summary, the primary components of end-of-life care for ICU nurses in the FGI were centered around ‘comforting’ and ‘connecting.’ The participants said that they aimed to provide comfort to patients by connecting them with their families, spiritual beliefs, social networks, and their life experiences, helping patients organize their thoughts and accept death without feeling isolated. These priorities were set in the context of the challenges faced in providing end-of-life care within the ICU's broader scope of care.

DISCUSSION

This study explored how end-of-life care is practiced by ICU nurses, who operate in an environment focused on active treatment-oriented intensive care and frequently encounter death situations [4]. Through the FGI of Phase I, referencing Kolcaba's comfort theory, the goal of end-of- life care was suggested. ICU nurses highlighted the essence of end-of-life care in connecting the patient's life journey to their final moments and facilitating meaningful time for patients and families. ICU nurses play a pivotal role in supporting families during this challenging phase, prioritizing communication, gathering crucial information, and providing extensive support [25]. Despite their demanding schedules, ICU nurses focus on activities that create a comforting environment for both patients and their families to ensure a meaningful end-of-life experience.

However, ICU nurses often faced situations where they must care for patients beyond recovery without clear guidelines, leading to ambiguity about their professional roles. In response, nurses employ ‘professional identity’ and ‘self-defense’ strategies to navigate these unpredictable treatment scenarios and continue providing end-of- life care [26]. Achieving a clear recognition and proficient delivery of end-of-life care by ICU nurses can help protect their professional identities and alleviate feelings of guilt.

The two groups for FGI, with different ICU experiences, exhibited variations in their approaches to end-of-life care. The more experienced group (Group 1) tended to emphasize comprehensive end-of-life care for both patients and their families, while the less experienced group (Group 2) tended to perceive end-of-life care in the context of general ICU practice. This distinction suggests a need for education in this area, considering nurses' ICU experiences.

In Phase II, the descriptive survey and IPA identified the priority and importance of end-of-life care in the ICU. Nurses highlighted the importance of creating dedicated spaces within the ICU, separate from critically ill patients, as a key factor in achieving their goal. Previous studies have supported the notion that nurses can adapt the ICU environment to establish a comfortable and peaceful setting for dying patients and their families, facilitating the provision of end-of-life care [15,27]. However, the absence of such dedicated spaces poses a significant obstacle to delivering dignified end-of-life care in the ICU.

In summary, this study revealed that ICU nurses recognized the importance of addressing spiritual, social, and psychological aspects in end-of-life care, aligning with previous research [28–30]. However, the ICU's work environment often prioritizes physical care due to its efficiency, hindering comprehensive delivery of holistic care. To bridge the gap between perceived and practiced end- of-life care, ICU nurses should collectively establish a clear professional identity, reducing ambiguity in their care-giving experiences. As the ICU has traditionally been a space focused on saving lives, there is a need to extend its support to ensure peaceful deaths, thereby harmonizing intensive care with end-of-life care.

Some limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the study included only 95 surveys for the IPA, which falls short of the recommended minimum sample size of more than 100 surveys for social science research [24]. However, it is worth noting that in the healthcare and nursing fields, previous IPA surveys have had varying participant numbers, ranging from approximately 50 to 400[31–33]. Furthermore, the participants were exclusively recruited from ICUs at a single university hospital in Korea. Consequently, the items of end-of-life care in ICU derived from FGI may vary depending on the specific ICU environment. Therefore, further research and discussions on this topic in more diverse ICU settings are warranted.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated ICU nurses' perceptions of end-of-life care, its practical implementation, and associated priorities using a mixed-methods approach that included FGI and IPA. This unique method revealed that ICU nurses aimed to offer comfort by connecting patients with their families, spiritual beliefs, social networks, and life experiences, facilitating acceptance of death amid the challenges within the broader scope of ICU care. Future endeavors should focus on developing tailored measures specifically designed for the unique ICU environments to enhance the quality of end-of-life care provided.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

AUTHORSHIP

Conceptualization and Methodology - Jung HJ and Chang SO; Data collection - Jung HJ and Kim D; Data analysis & Interpretation - Jung HJ and Chang SO; Drafting & Revision of the manuscript - Jung HJ, Kim D and Chang SO.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.